A Healthy Check-In with F.O.A.K. Reality - A Whitepaper from IPA

By Krista Sutton

It’s no secret that we are big fans of Independent Project Analysis (IPA) here at New Energy Risk. Their whitepaper entitled “The Successful Management of New Technology Projects”, authored by Ed Merrow, is a good example of why. Bringing data driven insights to the murky world of project management is a noble and underappreciated contribution to the ecosystem. In this world littered with spectacular project failures and fraught with advertisements for the newest project management fad promising all manner of miracle, IPA stands apart by bringing real-world, data-backed insights to help project professionals and organizations better develop and execute projects.

In this whitepaper focused on new technology (our favorite subject!), IPA calls out some of the common issues we at NER observe projects hitting as they go through development and execution, and offers some best practices to make sure your project doesn’t get too far over its skis.

#1: Data Is Key

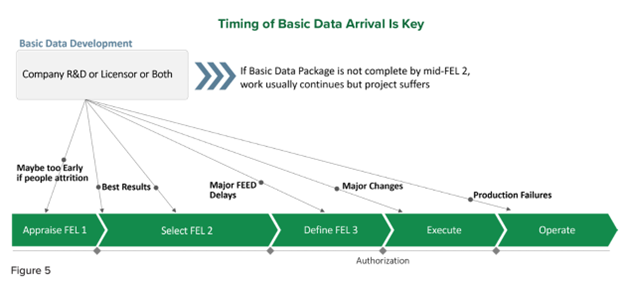

Too many times new technology companies will not have a fully developed basis of design, or it will be changed late in development or even (gasp!) during execution. Part of the basis of design documentation includes the heat and material balance summarizing the expected operating conditions and yields, and the definitions of feedstock & product composition and contaminants. Merrow refers to this as “Basic Data”. The basis of design is the heart of a project. The project has been set up to fail if there are any missing, unreliable or unrealistic data points, or if the Basic Data does not capture expected variability in the process, feedstocks, products or boundary conditions. While you and your team might execute the project flawlessly, if you have an incorrect or underspecified basis of design, you will still produce an asset with operability and reliability problems that underdelivers on project benefits. More often than not this either means investment to fix or, in the worst case, major write downs or even company bankruptcies.

As Merrow points out, project teams consistently overestimate how much Basic Data is available, especially in projects where the extent of technology novelty is not clear. He calls out “integration projects” where a commercially proven technology is being integrated into another commercial process and points out that such projects often underestimate the impact of that integration. IPA is even able to quantify this impact: 2.5% more unknowns in the heat and mass balance, 2.7% project cost growth, 0.5 months of additional startup time, and a 4.7% decrease in production after 7-12 months (based on nameplate design of 100%) [1]. It might sound acceptable but this effect is observed for EACH new integration, and BEFORE accounting for any new technology steps!

In response, it is recommended to pause development work and figure out a way to get the Basic Data required, i.e. through research, piloting, feedstock studies, cold flow studies, or field trials. The best practice that Merrow presents is to establish a “Basic Data Protocol” focusing on what is unknown (rather than a basis of design, which deals with what is known) and a process to obtain this data before heading into development work, to minimize repetition. Paul Szabo authored another relevant article on this topic, “Follow this Process Development Path “ [2], which discusses the benefits of completing a virtual commercial design, and then thoughtfully scaling that design down in a way that allows for all this data to be generated during piloting. The gaps in Basic Data need to be resolved before finalization of the design and the start of front-end engineering.

Merrow points out that a pitfall to be avoided, and one that NER has observed often, is a bias towards addressing data gaps with seemingly conservative design decisions such as extra spares or redundancy. This can give a false sense of security, whereas an empirical validation could have revealed potential causes of failure that exceed the conservative design assumptions or bypass them completely (e.g. unexpected contaminants). There is no guarantee that the right problem has been identified, all the consequences upstream and downstream have been accounted for, or how severe the problem might be at full scale. It can also make the project much more expensive without addressing the risk. It is the equivalent of wearing a helmet to ride a bike and finding yourself on a busy three-lane highway.

The first thing that NER looks for as part of due diligence is whether the project has performed the appropriate analysis, testing, piloting, and scoping to have a complete basis of design, and how that has been integrated into the engineering documentation. We have observed that where there is a lack of integrated pilot data, or sparse operational data, a project invariably ends up going back to do additional studies or repeat parts of the Front-End Engineering Design (FEED), or gets stuck in perpetual development, unable to move forward due to a lack of clearly defined project objective and data requirements.

Merrow provides a diagram in Figure 5 of his paper that nicely illustrates the effects of missing Basic Data.

#2: There is No Substitute for Development Work

Merrow has words of caution regarding the use of simulators and their applicability to predict the performance of different kinds of new processes. Simulators are useful for highlighting the important questions, but they are not a substitute for empirical process development work. When used properly, simulations can help narrow the range of experiments needed, and when calibrated against real world results, they can be beneficial in both the design and operation of a process. A common pitfall is trusting a model just because it seems precise and detailed, and not verifying the accuracy of modeling results against experimental lab and process data. Merrow points out an important observation: simulations are better at predicting the behavior of homogeneous materials, and are less capable if the process involves solids or heterogeneous mixtures. He concedes that examples do exist of process development leaping from bench scale to commercialization (citing up to 350,000X scale up!) with the aid of simulations, but these are the exception rather than the rule and success cases are confined to processes where the number of new steps are low and the process fluids are liquids and gases that are well studied with extensive property libraries. For most process development a pilot or a PDU (process development unit: a focused pilot where only the new steps are included) will be needed. Merrow offers these best practices for pilots and PDUs:

- All new process steps should be included.

- Any steps that have dynamic interaction with the new process steps should be included

- Any recycle streams and affected step should be included

- If the scale of the process step affects the behavior of the process (for example geometry, surface effects, flow regime, mixing etc) then you are likely to need to do a pilot at a larger scale. The essential principle here is to make sure that the equipment in the pilot or PDU adequately represents the larger-scale process.

To Merrow’s excellent points, I will add a fifth and sixth consideration based on NER’s experience.

- If you are innovating in an industry that expects meaningful sample sizes of on-spec product prior to executing an off-take contract (more common in solids processes or where your material will go into consumer products) or innovating in a nascent product market, you will need a fully integrated pilot, and it will need to be at the larger scale, which is typically referred to as a demonstration unit.

- If you have a heterogeneous feedstock that varies widely over time, then you will need a fully integrated pilot to understand variability effects on all the process steps, product quality, and yields.

In general, it rarely pays to skimp on piloting, and building a fully integrated pilot at the largest scale feasible will give the best outcomes in the commercial plant and avoid delays in the development process. In other words, do it right or be prepared to do it over.

#3: Solids are Hard (pun absolutely intended) - Plan Accordingly.

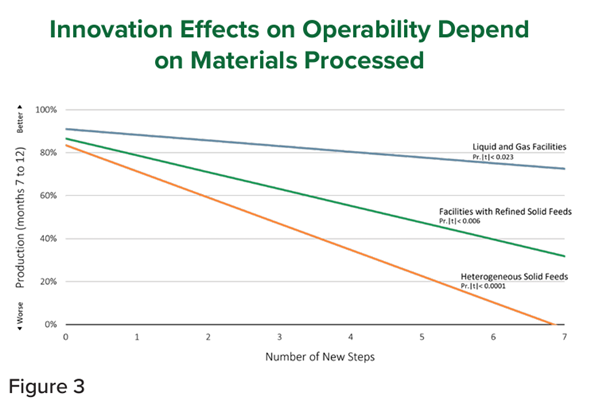

In the whitepaper Merrow, highlights the higher cost risk of new technology in the mining industry versus the chemical industry, and attributes this premium to the hard-to-model and often raw, unrefined, and heterogenous solid feedstock. In such industries Basic Data are expensive to develop and scaling is not always straightforward, so the scaling steps are naturally smaller leading to an increase in cost and time to develop, deploy, and scale innovative technology. Indeed, in Figure 3 from the whitepaper, shown below, Merrow paints the stark contrast between innovation outcomes in liquid and gas technologies versus technologies involving solids handling.

At NER, we have observed firsthand some common problems encountered during initial operations of new technology processes that involve solids handling, including modifications to solids handling process steps, the need for extra spare parts for solids steps, and even redesign due to solids carryover and plugging. The best practices here include limiting the amount of innovation you are introducing in a single project, performing integrated piloting including all solids handling steps, using equipment as close to the commercial scale and design as possible, and running pilots on real world feedstock with a wide range of realistic contaminants. In addition, it is important to recognize that even if you do all these things, you will still need additional contingency built into your start-up plan to cover inevitable solids handling issues when you are innovating in this space.

At NER we regularly see projects not planning for additional commissioning and start-up time in their financial models. This ultimately leads to unrealistic expectations from high-level stakeholders and a lack of funds to cover operating expenses or modifications when startup inevitably takes longer than advertised. This can lead to new technology companies needing to raise additional funds in the midst of commissioning just to continue operations.

Final Thoughts

In summary, this new technology focused paper from IPA gives us some very useful benchmarking tools for new technology projects and reminds us of the best practices and pitfalls associated with technology development and deployment. With the energy transition on an accelerated timeline and everyone hurrying to “deploy deploy deploy”, it is important to remember Professor Brent Flyvbjerg’s sage advice to projects from the highly quotable “How Big Things Get Done” [3]:

“Planning is relatively cheap and safe. Delivery is expensive and dangerous. Good planning boosts the odds of quick effective delivery, keeping the window of risk small and closing it as soon as possible”

Sources:

[1] Table 1, Merrow, E. W. & Independent Project Analysis, Inc. (2024, July). The Successful Management of New Technology Projects. https://www.ipaglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/New-Technology-White-Paper.pdf

[2] Szabo, Paul. (2013). Follow this Process Development Path. Chemical Engineering Progress, December 2013, 24-27

[3] Flyvbjerg, Bent & Gardner, Dan. (2022). How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors that Determine the Fate of Every Project from Home Renovations to Space Exploration, and Everything in Between. Penguin Random House 2023

The Case Against FOAK: Why you should stop calling your project a first-of-a-kind

By Ben Cader-Beutel

At New Energy Risk, we advise, evaluate, and insure projects being developed by climate tech innovators. And as the sector approaches a pivotal moment, with enhanced geothermal, third-generation biofuels and electrolytic hydrogen nearing project readiness, climate tech appears to be close to putting its awkward teenage years in the rear-view mirror.

There is a well weathered acronym that has taken on a new lease of life of late and is fast becoming lexicalized in innovation circles: “FOAK” (for “first-of-a-kind”). In vogue though it is, I believe the term is standing in its own way. Rather than fostering the deployment of novel technology into much needed infrastructure projects, FOAK has become the proverbial caution tape to project investors and lenders.

The Adoption of FOAK

We’ve seen a recent surge in sophisticated and well-funded climate hard-tech companies emerging from the low-interest rate COVID period. These firms are now transitioning from scrappy startups to fully-fledged developers, licensors, and equipment manufacturers (or a combination of all three). They are entering their deployment phase and encountering an underdeveloped ecosystem in comparison to their R&D and demonstration phases, which were supported by accelerators, a vast VC network, and government grant programs.

A key issue is the finance world’s inability to keep up with technology innovation, especially at the intersection of development and project finance. Early project returns do not match the significant capital outlay and perceived risk – at least in the eyes of conventional growth capital. And the industry has learned, through Clean Tech 1.0 that venture capital and SPACs are not good at building successful hardware companies alone.

“FOAK” is used by innovators and early-stage VCs to describe the project that takes the technology across the ‘valley of death’, through the ‘missing middle’. Much like catching the golden snitch, financing for such a project is unpredictable and elusive. While building the first commercial project is an important milestone in a hard tech startup’s journey and the beginning of sustainable returns for shareholders, it seems to me that the FOAK label has become more of a red flag to project investors than it is a signal for imminent growth.

FOAK’s Dilemma

I recently participated in an industry roundtable for a group of “FOAK EPCs”, “FOAK investors”, and “FOAK insurers”. The first agenda item was to define the term. Is it based on a bill of materials? The sponsor’s balance sheet? Feedstock source? As expected, everyone in the room had a different answer. This lack of consensus complicates the conversation; we can’t even agree on the pronunciation, for FOAK’s sake.

By my personal definition, a FOAK meets two criteria:

- The project includes any new technology or new integration of technology (even if the unit operations are all TRL-9 individually).

- The project generates enough cash to offer a positive return on investment.

But others in the ecosystem choose to include new geography, a new tax incentive, or a new offtake structure. Once you get broad enough, every project becomes a FOAK.

Reality is much more nuanced than any definition could capture. Projects are evaluated by investors and lenders individually and according to a robust set of criteria. Highlighting an aspect of project’s novelty limits its ability to attract such funding, even if it has proper mitigations in place for each of its risks.

FOAK is a large bucket, which tends to obfuscate important differences in technology and associated risk, calling out the ‘hair’ rather than the value. For example, flow batteries and cellulosic ethanol are fundamentally different projects, yet both are categorized similarly when seeking project capital. This alienates investors who may specialize in specific technologies or market segments and may in fact be able to understand the risk.

Beyond FOAK

Today’s terminology around project deployment calls out shiny novelty rather than value. The entire innovation ecosystem – startups, capital, and government – has a role to play in deploying new technologies, and the future of climate tech (and our planet) depends on making projects appeal to investors motivated by reliable returns.

So, what’s the solution? Shifting away from the FOAK terminology towards a more nuanced presentation of the spectrum of risk and respective mitigations could position projects to access broader pools of capital. With the proper tools in place, such as hybrid equity enabling investors to tap into future upside (see Twelve and Infinium’s recent raises), or project-centered risk mitigation tools such as NER’s performance insurance solutions, projects can abandon today’s unhelpful platitudes in favor of a carefully constructed scaleup strategy.

How Often Do Batteries Catch Fire?

By Shawn Lee

How often do batteries catch fire? There is a lot to this seemingly simple question. Battery systems can cost 100s of millions of dollars. Between 2017 and 2019, South Korea had 23 battery fires across multiple battery providers. LG Chem, one of the world’s premier battery manufacturers, lost $124M on its energy storage business in the first quarter of 2019 after seven consecutive quarters of profits. An Energy Ministry inquiry suspended five of the country’s 1,490 energy storage facilities during its audit, blaming poor installation quality, incomplete electrical shock protection, and a lack of overall controls for integrated systems. [1]

Lithium-ion batteries, the most common type, store energy by moving lithium ions between an anode comprising a high energy state material (generally some sort of neutral graphite) and a cathode comprising a low energy holding material (some kind of oxide). These two materials are kept electrically separated, which forces the electrons to flow in an outside circuit, where these electrons ultimately power anything from a lightbulb to a full electric car.

If for, whatever reason, the battery forms an internal electrical connection between the anode and the cathode, the battery will discharge all its energy through this short circuit in an uncontrolled fashion. This internal short circuit can be created by degradation due to the Battery Management System repeatedly discharging the battery too quickly or operating it out of its temperature range, or due to some sort of manufacturing fault. Either way, once the battery creates an internal short, it discharges a bunch of energy very quickly, and generates enough heat to boil liquid hydrocarbon electrolyte that separates the two materials (which incidentally is normally carcinogenic).

In most properly designed battery cells, the cell will vent the hydrocarbon vapor through pressure relief points. If the cell isn’t properly designed, the battery cell could burst in an unexpected way. In both cases, there’s now a hot hydrocarbon vapor mixing with atmospheric oxygen, which is perfectly capable of conflagrating and overheating the nearest intact battery cell and causing it to burn as well.

Very quickly, the effect can be a runaway fire burning from unit to unit. Developers can mitigate this by installing the batteries outdoors, using active fire suppression systems, separating clusters of battery units in space, and actively monitoring key parts of the battery and proactively taking parts offline and replacing them before they cause a fire.

When a battery fire happens, it’s a very high-profile event. The fire is typically very hot, can burn for longer than other kinds of fires, and the event can erode public support for new battery systems because they’re perceived as less well understood. Of course, no power technology is immune from fire.

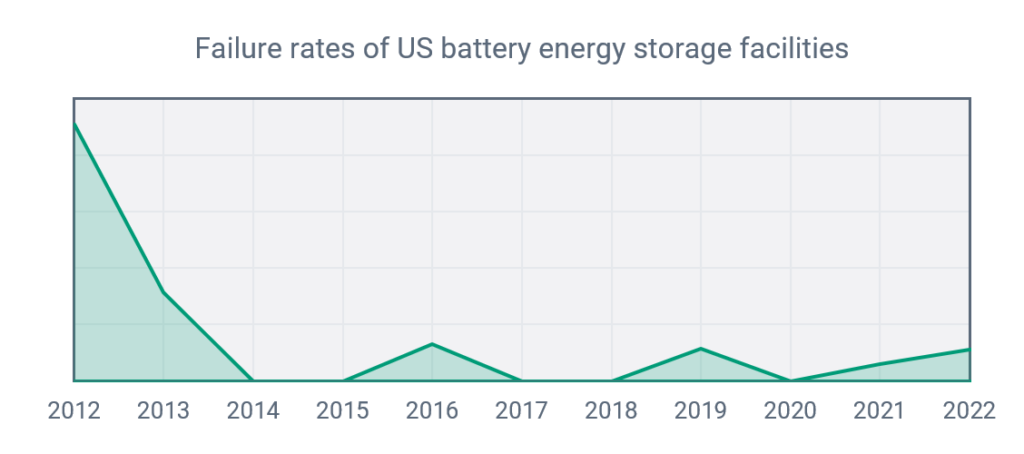

The good news, however, is that as an industry, we are no longer really in the wild west of battery fires. The frequency of large battery fires is easy to find, since they almost always make their way into the news. Fire data reported by the Electric Power Research Institute [2] combined with data on installed batteries in the United States from the Energy Information Administration, gives us a true sense of the yearly rate of failures. Large changes to the failure rate year on year are indicative of an immature industry still working out its kinks.

The battery industry reflected an immature industry before 2014. However, since then, US BESS failure rates have been relatively consistent, showing that even though we’ve yet to settle on a consensus on fire codes, internationally or within the United States, the battery industry overall has settled into a consistent fire rate. Of course, when they do happen, fires can be catastrophic and design practices play a part in limiting both the occurrence of fires, and their consequences.

At NER, we use an understanding of battery failure rates, and a technical understanding of individual root causes and mitigations, to support battery projects with warranty backstops and Battery Dispatch Insurance products which can supplement standard property covers and help batteries deploy at scale.

Sources:

[1] https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/trending/bVy2KGU3Opsle5Vv8QG0-Q2

[2] https://www.pv-magazine-australia.com/2021/09/28/australias-biggest-battery-cleared-for-testing-following-fire-fallout/

Interview: Sue Coates, Trident Public Risk Solutions

Interview: Sue Coates, Trident Public Risk Solutions

We are inspired by people who are passionate about insurance, project finance, and technology that solves pressing global challenges. In this interview series, our chief actuary, Sherry Huang, talks with friends of New Energy Risk whose work makes a difference, and whose journeys will inspire you, too.

Sue Coates serves as the President of Trident Public Risk Solutions, member of Paragon Insurance Holdings. During Paragon’s recent ‘Sleep-Out’ event to raise money for homeless shelters for teens, Sue led and joined a large team and supported the cause by example. Ever since New Energy Risk joined the Paragon group, I heard great things about Sue and her leadership. I had the privilege of speaking to her recently to find out about how she got to where she is today, what she thinks of effective leadership, and what she is looking forward to in 2024.

Sue Coates serves as the President of Trident Public Risk Solutions, member of Paragon Insurance Holdings. During Paragon’s recent ‘Sleep-Out’ event to raise money for homeless shelters for teens, Sue led and joined a large team and supported the cause by example. Ever since New Energy Risk joined the Paragon group, I heard great things about Sue and her leadership. I had the privilege of speaking to her recently to find out about how she got to where she is today, what she thinks of effective leadership, and what she is looking forward to in 2024.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Please tell us a little about how you got to where you are today.

I started my career with a humble beginning as a representative at an independent insurance agency in personal lines. I quickly found I had a knack for understanding insurance contracts and was good at providing customer service. After a few years, a former colleague of mine recruited me to an MGA with a specialization in public entity insurance solutions, which is how I started in this space. This MGA was later acquired by Trident Public Risk Solutions. Over the last 16 years, I worked my way up from an underwriter to a manager, to an underwriting director, and eventually the President. Trident was acquired by Paragon in 2020 and we are now part of the Paragon MGA platform.

What are some unique aspects of providing insurance solutions for public entities?

Public entity is a great class of business that requires highly specialized knowledge to serve. Trident offers a wide range of insurance solutions to municipalities, public water/wastewater treatment utilities, counties, and public schools. As funding for insurance premiums is supported by taxpayers, our accountability standard is steep. We strive to help agents and policyholders manage through an evolving insurance landscape and make sure they have access to appropriate insurance solutions. Many of us at Trident have developed a personal connection and a deep appreciation for public servants. We are committed to the long-term stability of the program.

What is your leadership style?

I am a people-first leader, or you can say a servant leader. My goal is to become a resource at every level for all stakeholders in our business. As a leader, my job is to clear barriers and allow people to expand their intellectual curiosity and fulfill their career aspirations. In my own career, the first transitions to management and leadership were both hard – I had to let go of being the first point of contact and make sure to leave space for people to grow and develop. My clock/horizon is different from my team – I need to look ahead in the future and be attentive to the ‘WHY’ and ‘HOW’ in everything we do. I make sure my leadership team has complementary skills, so we can benefit from different ways of looking at the business.

Would you tell us about your sleep-out experience with Covenant House supported by Paragon?

I am thankful that Paragon sponsored this event for Covenant House, which is an organization that provides support and shelter for youth homelessness. I am grateful that I was able to share this sleep-out with my colleagues and it is definitely a unique and powerful team-building experience. Some of the personal sharing from people who benefited from Covenant House’s support was very moving, and reminded us all to stay humble of what we have and pay it forward.

What are your goals for the company in 2024?

Create more value for our customers, grow the team to continue to enhance our capabilities and provide high quality solutions.

The US Treasury Releases Guidance on SAF Emissions Rates, but How Many Questions Does it Answer?

By Krista Sutton – Principal Process Engineer

Last week, the Treasury released their long-anticipated guidance [1] on emissions rate calculations for the 40B sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) tax credit established by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which is likely to serve as a model for the 45Z clean fuel tax credits with regards to SAF (although such guidance has not been issued, or equivalency explicitly indicated). Let’s dive in…

What is at stake?

Under Section 40B, the IRA established a tax credit value of $1.25 per gallon of SAF, meaning aviation fuel with an emissions rate at least 50% lower than fossil jet fuel. The act includes an adder of 1¢ per additional percentage-point reduction beyond 50%, up to a maximum of $1.75 per gallon. Section 40B makes tax credits available through the end of 2024.

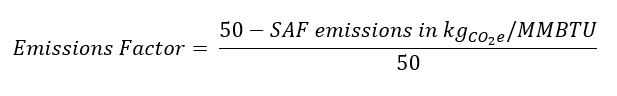

Under Section 45Z, also newly created by the IRA and which makes tax credit available from 2025 through 2027, credit value is calculated as an emissions factor multiplied by an applicable amount, which for SAF is $1.75 per gallon. The emissions factor is calculated as follows, meaning that tax credit value accrues from a baseline emissions rate of 50 kgCO2e per MMBTU.

The SAF emissions are calculated through a lifecycle analysis (LCA) methodology – a topic of much debate. At the heart of the issue is whether corn-based ethanol-to-jet production and soybean oil-to-jet production will qualify for the tax credit. The guidance around LCA methodology will ultimately determine how competitive 13.8 billion gallons a year of US ethanol production [2] would be with respect to other feedstocks for the production of SAF.

Why is there an argument?

A debate has been raging since the passage of the IRA over which lifecycle analysis modeling methodologies should be accepted to estimate SAF emissions. Sections 40B and 45Z specifically call out the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) methodology:

“the most recent Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation which has been adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization with the agreement of the United States, or…”

but leaves room for debate in the following paragraph:

“any similar methodology which satisfies the criteria under section 211(o)(1)(H) of the Clean Air Act (42 U.S.C. 7545(o)(1)(H)), as in effect on the date of enactment of this section.”

On one side of the debate, the biofuels industry and airlines have argued for the inclusion of the ANL-GREET (Argonne National Labs (ANL) Greenhouse Gas, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation) model which is used as the basis for lifecycle analysis for all the other low carbon fuels eligible for the 45Z tax credits. These stakeholders cite its more frequent update cycle and more recent datasets containing the most up-to-date advances in the industry. [3]

On the other side, environmental groups have argued that the GREET model is not as stringent in accounting for emissions resulting from indirect land use change (ILUC) as the ICAO CORSIA methodology, and that the use of the ANL-GREET model would grossly undercount emissions from a land use transition to grow crops for SAF production. [4]

What is the difference between the models?

Estimates for direct emissions from these models are actually quite similar, as a version of GREET was used to derive the default LCA factors by the ICAO. However, there are key differences related to the modeling of input assumptions for indirect emissions between the ANL-GREET and ICAO CORSIA methods; specifically:

- How the two models develop the ILUC factors;

- The allowed land-use basis;

- The data referenced for each type of land use conversion; and,

- Whether they give credit for sustainable farming practices via soil organic carbon (SOC) modeling.

These assumptions can make a large difference in the final emissions numbers according to the International Council of Clean Transportation:

“ILUC modeling cited in some configurations of the default GREET model estimates land-use emissions for corn ethanol and soy that are only 25% – 33% of the total emissions estimated through public regulatory assessments by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the California Air Resources Board” [5]

So, what did the guidance say?

A likely less contentious part of the guidance establishes a safe harbor for fuels that qualify for D4, D5, D3, or D7 Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs) under the incumbent renewable fuels standard (RFS) administered by the EPA. Fuels meeting D4 or D5 certification will be automatically considered to have a 50% emissions reduction and fuels meeting D3 or D7 certification will be considered to have a 60% emission reduction for the purposes of 40B credits.

On the modeling side, the guidance, at least on the surface, has handed a win to the airlines and biofuels industries, and particularly ethanol producers that are transitioning to SAF production, by authorizing a GREET-based model as an acceptable alternative for determining the life cycle GHG emissions of SAF. In reality, they have kicked the can down the road as the guidance references a new GREET model being developed to meet the criteria of 40B that is planned to be released on March 1st, 2024. The updated model could incorporate more stringent indirect land-use change factors. This would effectively authorize the use of the GREET model (what the industry wants) and implement stricter ILUC factors (what environmental groups want). For now, it leaves the door open for a wider pool of crop-based SAF to qualify for 40B credits so we can be sure that the debate will continue, and we will see which way the pendulum swings on March 1st, 2024.

Sources:

[1] https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1998

[4] https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ID-16-Briefing-letter-v3.pdf

[5] https://theicct.org/long-shadow-model-inputs-could-dilute-ambition-of-saf-grand-challenge-nov23/

Split-Form Contracting: A Project Contracting Form Extolled by Experts, But Can Investors and Lenders Accept It?

By Brad Price - Managing Director of Technical Due Diligence

New Energy Risk helps accelerate the commercialization of industrial technologies that are solving global challenges. We routinely see that one of the biggest challenges to developing a bankable project is the contracting structure for engineering, procurement and construction. Conventional wisdom holds that a lump-sum EPC contract is superior, but the data presents a challenge to this assumption.

This blog post comes with a book recommendation – Ed Merrow, the Founder and President of Independent Project Analysis (IPA), recently published a great book called “Contract Strategies for Major Projects: Mastering the Most Difficult Element of Project Management.” I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in gaining new-found, evidence-based understanding of contract strategies for industrial projects that challenges conventional wisdom.

This blog post comes with a book recommendation – Ed Merrow, the Founder and President of Independent Project Analysis (IPA), recently published a great book called “Contract Strategies for Major Projects: Mastering the Most Difficult Element of Project Management.” I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in gaining new-found, evidence-based understanding of contract strategies for industrial projects that challenges conventional wisdom.

What is split-form contracting?

Ed defines split-form contracting as a structure that separates the construction activities (the C of an EPC contract) from the engineering and procurement activities (the E and the P) by using separate firms and contracts [i]. Under this structure, the EP firm has no role in construction, other than to field design clarifications, and performs no construction management activities. In nearly all case, EP activities are undertaken by the same firm as the Front-End Engineering Design (FEED) performed during project development, prior to the execution of the EP contract. According to Ed, the split form approach accounts for almost 30% of industrial projects [ii].

Split-form contracting can be performed on a lump-sum basis for each contract (lump-sum EP and lump-sum C), which has the potential to provide the contractual cost certainty that project finance transactions require – which is of great interest to NER and anyone aiming to conduct a project financing.

The Strengths of Split-Form Contracting

Ed uses the extensive IPA project database to compare the many different forms of contracting, such as lump sum EPC; engineering, procurement, and construction management (EPCM); reimbursable EPC (an EPC contract reimbursed on a time and materials basis); and split-form contracting. What stands out from the data is the cost competitiveness of the split-form contracting method. While lump-sum EPC contracts are generally lauded as the gold standard in the finance community, in fact a properly executed split-form contracting structure can deliver significant advantages [iii]:

- Split-form contracting is on average approximately 7% less costly compared to a lump-sum EPC contract. Reimbursable EPC and EPCM contracts are more costly than the lump-sum EPC approach, by approximately 13% and 7%, respectively.

- Split-form has less cost variability, with a standard deviation of approximately ±13% compared to lump-sum EPC (±25%), reimbursable EPC (±30%) and EPCM (±25%).

Split-form contracts do demonstrate slightly higher final cost growth compared to the original estimate compared to lump-sum EPC contract (4% vs. 1%) but the original cost estimate is on average so much lower that the overall 7% cost advantage mentioned is maintained. This cost growth should be handled with a slightly larger project contingency. For reference, the average cost growth for reimbursable EPC and EPCM structures are 7% and 6% respectively.

Regarding schedule, lump-sum EPC and split-form with lump-sum EP with lump-sum C take about 4% longer than reimbursable EPC and EPCM [iv].

Ed cites many reasons for the advantages of split-form contracting. One is that it prevents construction from starting before the engineering is completed. When engineering is late under a lump-sum EPC structure, the firm is highly incentivized to start construction despite not being ready [v]. This is because there is oftentimes a milestone payment associated with the start of construction. The result is extremely poor labor productivity for a variety of reasons, such as poorly ordered work and re-work.

IPA’s research uncovered another interesting advantage of split-form: projects that make extensive use of modularization exhibit even more pronounced cost advantages. This observation was significant because prior IPA studies had not indicated cost benefits for modularization under any other contracting approaches. Ed concludes that the savings associated with modularization must end up with the contractor under lump-sum or EPCM arrangement, whereas the split form allows the savings to benefit the owner [vi].

Why utilize split-form when lump-sum EPC is readily accepted by financiers?

It is NER’s experience that industrial projects comprising new technologies struggle to find a willing counterparty for a lump-sum EPC contract. The key concern we hear about is that the contractor is reluctant to take on the lump-sum construction cost risk. Many contractors are more willing to agree to a lump-sum contract for the engineering and procurement only. Essentially, there are very few firms willing to work on a lump-sum EPC basis, and even fewer where a new technology is involved. The split-form approach opens the doors to more counterparties willing to contract on a lump-sum basis for a partitioned scope and, furthermore, can actually deliver better results overall as demonstrated by the IPA dataset – it can provide more cost certainty than a EPCM or a reimbursable EPC contract structure and may realistically be the only way for some projects to move forward.

Key challenges when utilizing split-form contracting

There are challenges associated with the split-form method that may represent significant roadblocks for unsophisticated developers. Foremost among them is that the project developer needs to understand construction management and select the construction company. For many technology developers, their first commercial scale plant may be their first experience of managing the construction of a large industrial site. This will require the owner team to hire employees with these necessary skills and put in place the necessary management systems. The construction management does not need to be performed by the owner, but they will need to be more involved than they would with a lump-sum EPC contract and will need to staff the project appropriately. A general contractor can be hired to perform the day-to-day construction management for the owner organization but will require close involvement of the owner’s project managers.

Structuring the contracts in a split-form is not trivial. There needs to be a well-defined division of responsibilities between the firms related to commissioning, startup, and performance testing. The schedules and associated guarantees need to be carefully coordinated to ensure the engineering and procurement deliverables are available when needed for the construction contractor. The liabilities need to also be coordinated in a way that covers all the risks effectively and places the responsibility on the correct counterparty. Both the EP firm and the C firm need to offer liquidated damages related to hydraulic performance. Thermal performance guarantees need to be offered by the EP firm at least, and maybe the construction firm as well. Any construction problems discovered during commissioning (after Mechanical Completion) need to be the responsibility of the construction firm and should be linked to their schedule guarantees. Chemistry guarantees may be picked up by the EP firm, but it is more likely that the chemistry guarantees will only be forthcoming from the technology licensor and be passed directly to the owner. As a result, the penalties from the technology licensor will be small compared to the overall project value.

The way the performance guarantees are split and shared between multiple parties will give pause to many financers. The splitting of these guarantees will also reduce the liquidated damages available for any underperformance. A performance insurance product from New Energy Risk can be used to effectively “wrap” all these performance guarantees and provide the performance certainty needed by many capital sources.

An experienced perspective on split-form project execution

To gain an experienced perspective on how to execute on a split-form contract in a project finance transaction, I reached out to Antoine Schellinger, Executive Vice President of Project Operations & EPC at Citroniq. Antoine agreed that a correctly executed split-form project would “materially reduce the cost of project implementation,” but added that there are many challenges that need to be carefully managed to make it possible (many of those are mentioned in the previous section). He suggested the following example of how to execute a project by implementing the following split-form structure in place prior to a final investment decision (FID):

- Execute a lump sum EPF (engineering, procurement, and module fabrication) contract. The fabrication contract can be separated from the EP contract, and according to Ed’s book there are significant cost advantages for doing so.

- Execute a ‘good faith’ construction contract with an estimated cost based on estimated quantities, but with all commercial terms and conditions firm.

- Convert the construction contract to lump-sum when drawings are ‘Issued for Construction’ based on actual quantities.

- Hold a calculated equity reserve to account for growth in the construction contract that accounts for every reasonably foreseeable growth allowance (there are excellent historic metrics available).

The reason to delay the finalization of the lump-sum price on the construction contract is that final engineering drawings and accurate material costs are not available for the construction contractor at FID. As a result, the construction contractor will need to include a significant “risk premium” on the price if the lump-sum price is finalized at FID. Waiting to finalize this price can significantly reduce the risk premium and reduce the overall cost to the project.

Making split-form contracting ‘bankable’ for project financing

An important question for the energy transition and project finance ecosystem is whether the advantages of a split-form contracting approach can be adopted into project finance transactions. A key component to project finance is contracted cost certainty, which is why the lump-sum EPC contracting method is preferred (despite a high frequency of cost overruns, especially in poorly defined projects). While split-form contracting may be effective in reducing costs, it must be done in a way that also provide project financers with confidence that complete project scope is contracted at a fixed price. There must be complete confidence that these contracts, when combined with the owner’s contingency, enable the project to be completed within the project budget.

In NER’s view, financial institutions should consider a carefully structured split-form project as an alternative to lump-sum EPC, especially considering all the advantages it offers. Despite the multitude of benefits, there may be unsophisticated, or “check the box,” financers that are unwilling to invest in a split-form contracting project. To move the many projects forward that are needed to transition our economy to a more sustainable one, financers will need to learn more about split-form contracting and how it is executed effectively. Project developers will carry the same burden, carefully developing projects in a way that lowers capital costs while also providing the cost certainty that the finance markets require. In support of split-form contracting, NER is well positioned to help overcome the performance guarantee challenges that are unique to this contracting structure and is one of the many ways that we are Underwriting a Greener Future®.

Works Cited

[i] Merrow, pg. 56

[ii] Merrow, pg. 75

[iii] Merrow, pg. 65

[iv] Merrow, pg. 68

[v] Merrow, pg. 106-107

[vi] Merrow, pg. 107-108

Can the US Look to the East for Lessons in Wind Deployment?

By Britti Paudyal

Taiwan is implementing an ambitious program of offshore wind development and has had to take some bold steps to make it happen. Meanwhile, the US aims to achieve similar goals.

When I began my education in Climate Science at Minerva University, an undergraduate program based in San Francisco that takes me to seven different countries over four years, I expected that my learnings in Cleantech advancements would be concentrated mostly in the US and in Europe. Flying over the wind-turbine-clad coasts of Taiwan, I realized that my Eurocentric misconceptions about the state of the renewable energy transition in Asia were unfounded. My semester living on the beautiful island of Formosa sparked my curiosity to learn more about Taiwan's efforts in deploying wind to clean up its energy industry.

Taiwan, a strong US ally in Asia, boasts one of the world's largest hardware industries and a population of 23.5 million who enjoy an exceptional (and carbon-rich) quality of life. The country has a carbon footprint of 12 metric tons of CO2 per capita, only slightly lower than the American average of 16 tons [1]. With regards to sustainability-related attitudes and climate action, the nation boasts incredible amounts of public green space, highly reliable and efficient public transport, and ranks second globally in residential recycling, only after Germany.

Despite these successes, Taiwan's energy sector lags behind. With 98% of its energy coming from imported oil and gas from the Middle East, Taiwan faces the energy trilemma — a threat to energy security, affordability, and sustainability. Fossil fuels not only contribute to climate change and harm human health but also expose the isolated Taiwanese grid to significant risks of power shortages. Persistent tensions in the Gulf may manifest in shipment delays and supply shocks that could greatly impair Taiwan. Formosa is making strides toward cleaning up their energy industry considering these vulnerabilities and striving for greater energy independence [2].

Recognizing the potential for deep waters and coasts to harness wind power, Taiwan is leveraging the expertise of European wind developers to deploy multi-billion-dollar offshore wind projects up to 60 kilometers into the Taiwan Strait. Prominent off takers for these projects include TSMC, the world's largest contract chipmaker and Taipower with 20-year guaranteed Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) contracted at a fixed rate. Major wind energy builder Orsted from Denmark developed the Greater Changhua 2b and 4 projects, totaling 920 MW, reported to be the world's largest corporate offshore wind purchase power agreement [4] [3].

These undertakings have not come easy. To carry out offshore deployment, Taiwan undertook a risk-reward analysis, specific to their own situation. They have confronted barriers to implementation comparable to the US. In 2012, Taiwan enacted a comprehensive three-phase, 20-year “Thousand Wind Turbines Project” with a clear road map towards achieving 40-55 GW of offshore wind by 2050. Taiwan is amending its laws to allow wind farm construction up to 60 miles into deep waters, despite territorial risks from Beijing. Additionally, regulatory changes that allow foreign investors to own 100% of wind power stocks have been crucial to attract investment, accelerating the vast amounts of financing required for wind deployment [4,5].

There are many similarities between Taiwan and the US. President Biden aims to deploy 30 GW of offshore wind in the US by 2030, which presents significant opportunities to clean up the energy industry, create jobs, and spur investment across the supply chain. However, wind developers in the US face unique regulatory challenges. Although proposed wind energy projects total 18GW – over half the projected requirement to meet the 2030 offshore wind goals – the permitting process for wind construction on federally protected waters remains lengthy, burdensome, and ambiguous [6]. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) follows a four-phase process for offshore wind construction, including planning (2 years), leasing (1-2 years), site assessment (5 years), and construction and operations (2 years). In total, this process takes at least 10 years [7]. Although the Biden administration introduced the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Energy Permitting Reform to streamline the onerous federal, state, and local requirements for projects, these changes will take time to come into effect after the approval of the debt ceiling bill [8].

The Jones Act of 1920, a century-old law that requires only US-built, crewed, and flagged ships to transport cargo within the country, poses a unique obstacle to offshore wind projects [9]. Passed after World War I to protect the critically strategic US maritime industry, the law now hinders offshore construction by forcing project developers to charter from a pool of 32 turbine installation vessels under the EU flag at a rate of up to $180,000 a day and to perform logistical feats to avoid landing at US ports [10]. As an example of unforeseeable consequence, the Act has become a barrier to domestic and international trade, resulting in inefficiencies and missed opportunities for growth.

To install offshore wind turbines in deep waters, specialized vessels costing over half a billion dollars are required [11]. To avoid the restrictions of the Jones Act, Dominion Energy developed its own 14,000-ton steel vessel at a cost of $500 million to install the country’s first full-scale commercial offshore wind farm [11]. Between four and six additional specialized installation ships are needed to meet the 2030 offshore wind goal of 30 GW, which requires the construction of 2100 turbines [11]. Developers are hesitant to build these vessels due to their high cost and the need for constant demand over decades to recoup the initial investment. The Jones Act, along with the lengthy permitting and approval process of NEPA and BOEM, highlights the need for solutions to work around or adjust policies that impede offshore wind deployment.

Taiwan's pipeline of 11 offshore wind farm projects totaling 5.7 GW by 2025 is a stark contrast to the United States' mere two operational farms (Block Island Wind Farm in Rhode Island and the Costal Virginia Offshore Wind pilot facility in Virginia). Taiwan is achieving its goal thanks to its ambitious national targets, swift regulatory amendments, and willingness to collaborate with foreign developers such as Orsted, using vessels such as Seajacks Scylla, who deployed the 111 wind turbines for the Changhua 1 and 2a offshore farms (900 MW) [13,14]. The US has much to learn from Taiwan's offshore wind success, which highlights the importance of integrating ambitious objectives and billions of dollars in funding with streamlined project approvals, permits, and regulatory changes to allow for efficient utilization of global industrial capacity or the development of domestic capability [12].

References

[1] Knoema . (n.d.). Taiwan Province of China CO2 emissions per capita, 1970-2022 - knoema.com. Knoema. Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://knoema.com/atlas/Taiwan-Province-of-China/CO2-emissions-per-capita

[2] Hou, E. A. F., Jen-yi, & Hou, E. A. F., Jen-yi. (2020, April 27). Overcoming Taiwan’s Energy Trilemma. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/04/27/overcoming-taiwan-s-energy-trilemma-pub-81645

[3] Wu, S. (2023, May 10). Taiwan’s wind industry braves cross-strait risks in clean energy boom. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/taiwans-wind-industry-braves-cross-strait-risks-clean-energy-boom-2023-05-10/

[4] Davies, N., Julien, B., & Rebbapragada, A. (2020, October 30). Industry seeks to replicate Taiwan wind success throughout Asia | Global law firm | Norton Rose Fulbright. Www.nortonrosefulbright.com; Petroleum Economist – Energy Transition Newsletter. https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/1f7442e2/industry-seeks-to-replicate-taiwan-wind-success-throughout-asia#section1

[5] Chiang, Y.-M. (2023). The Legitimacy and Effectiveness of Local Content Requirements: A Case of the Offshore Wind Power Industry in Taiwan. Springer Climate, 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24545-9_8

[6] US DOE. (2022, August 16). Offshore Wind Market Report: 2022 Edition. Energy.gov; Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy. https://www.energy.gov/eere/wind/articles/offshore-wind-market-report-2022-edition

[7] Gov, B. (2020). The Renewable Energy Process: Leasing to Operations. https://www.boem.gov/sites/default/files/documents/renewable-energy/Leasing-Process_0.pdf

[8] Nilsen, E. (2023, May 24). What is permitting reform? The critical energy provision buried in debt-ceiling negotiations | CNN Politics. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/24/politics/energy-permitting-debt-ceiling-climate/index.html#:~:text=Energy permitting reform could rethink

[9] Duncan, C. (2023, April 3). The Jones Act: How a 100-year-old law complicates offshore wind projects. Spectrumlocalnews.com; Spectrum News 1. https://spectrumlocalnews.com/nc/charlotte/news/2023/04/03/the-jones-act--how-a-100-year-old-law-complicates-offshore-wind-projects#:~:text=The current guidance on the

[10] Grabow, C., Manak, I., & Ikenson, D. (2018, June 28). The Jones Act: A Burden America Can No Longer Bear. Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/jones-act-burden-america-can-no-longer-bear

[11] Shields, M. (2023). Supply Chain Road Map for Offshore Wind Energy in the United States. Www.nrel.gov; National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

[12] Hu, A. (2023, July 11). Biggest offshore wind farm in the US gets the go-ahead. Canary Media. https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/wind/biggest-offshore-wind-farm-in-the-us-gets-the-go-ahead

[13] Kuo, J. (2021). Taiwan Offshore Wind Farm Projects Update. Www.jonesday.com; Jones Day. https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2021/08/taiwan-offshore-wind-farm-projects-update

[14] Durakovic, A. (2022, April 1). First Turbine Stands at Greater Changhua 1 & 2a Offshore Wind Farm. Offshore Wind. https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/04/01/first-turbine-stands-at-greater-changhua-1-2a-offshore-wind-farm/

An Exciting Week in Material Science

By Shawn Lee.

Some intriguing claims by Korean superconductor researchers hold lessons ion the importance of verification in academia and in industry.

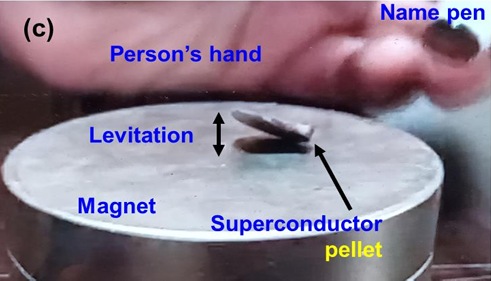

Alleged partial levitation of an LK-99 sample [1]

On Friday afternoon, three Korean researchers released two pre-prints (draft papers not yet reviewed by third party peers or editors) claiming to have made a superconductor that works at room temperature and pressure [2]. This is an exciting claim; superconductors can conduct electricity without any resistance or loss. In theory, these materials could dramatically increase the efficiency of electricity transmission and electronics, low-friction transport, nuclear fusion, and quantum computing. In practice, all currently published superconducting materials only show their special properties at very low temperatures. In 2021, the highest temperature superconductor was a fragile cuprate of mercury, barium, and calcium at -140C.

Assessing claims of high temperature superconductivity in public is similar to how we assess claims of technical performance at New Energy Risk. Like many exciting developments, the record around this possible discovery is still emerging. The original papers were the product of a collaboration between a university professor and industrial R&D postdocs. One of the original two papers drafts was recalled, and the author who originally brought it to the public turns out had been fired a while ago. The industrial partners may have held back key parts of the manufacturing recipe, or at the very least released a substantially non optimal study [3].

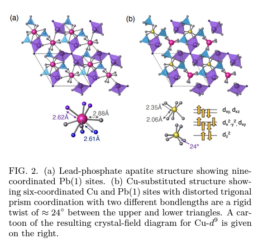

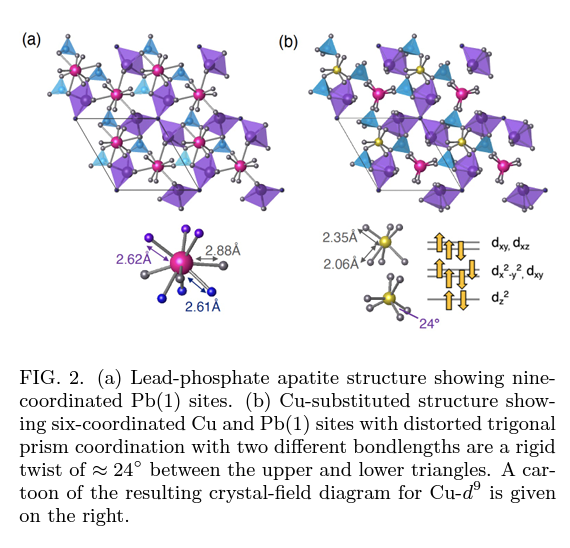

There are two aspects of a technical claim that need to be validated. The first is theoretical: is the claim possible under the laws of physics, and under what conditions? The second part is empirical: can we show with data that this really happened? On the theoretical side, the original paper speculated, without quantum-mechanical simulations, that adding trace amounts of copper caused the material structure to deform enough to create superconducting states. On Monday, teams from Argonne National Lab and Northwest University in Xi’an both ran density functional theory quantum simulations that showed two possible reasons why room temperature superconductivity could be possible with materials in the original paper [4]. This is interesting because prior to this, superconductors generally came from altered conductors, whereas the base material before copper addition here, apatite, is an insulator, and both papers showed that while the superconducting state is possible, it competes with non-superconducting states and is not preferred.

Simulated distortions by substituting Copper centers [5]

On the experimental side, the original papers did not actually measure zero electrical resistance or the full expulsion of the magnetic field from the material that would be key signs of superconductivity, but did include partial levitation on top of a magnet, which could indicate regions of superconductivity at room temperature. Unlike most other superconducting candidates, these materials can be produced over the course of days. The fanciest piece of equipment necessary is a chemical vapor deposition chamber, which is common in most semiconductor labs and means that we should have results from third parties within a week.

The first experimental results from third parties are a mixed bag. The first one in pre-print, from Beihang University, showed no sign of superconductivity at room temperature as claimed, while claiming a purer version of the material than the original Korean papers [6]. Other results announced, but not written up, show mixed results ranging from optimistic to no noticeable effects at all, with the most optimistic case showing as zero resistance at 110K (well below the originally advertised transition temperature) [7]. Nothing, including the original papers, has been peer reviewed, but even that’s not a guarantee. In 2022, another team’s high temperature superconducting paper had to be retracted from Nature after publication because of falsified data.

Between the theory and the mixed bag of early experimental results, it’s certainly interesting enough to continue investigating. My guess right now is there may be some local states which may display some superconducting characteristics, but the difficulty in isolating those regions may make replication harder than in other materials. As the picture of what’s actually happening in these materials emerges, we see similar themes to how NER underwrites any new technology: we make sure it’s physically possible at least in theory - even if the precise causal mechanism is unknown - and then we make sure that key claims have been validated experimentally by third parties, and that the method reporting is sound and consistent with best standards.

That’s clearly not yet the case here. There are probably years of process engineering improvements and characterizations before a verified discovery becomes an insurable commercial technology, but this is a reminder of the importance of verification procedures, both in academia and in industry.

Cited Works

[1] https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/2307/2307.12037.pdf

[2] https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/2307/2307.12008.pdf

[3] https://www.tomshardware.com/news/superconductor-breakthrough-replicated-twice

[4] https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.16892 and https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.16040

[5] https://arxiv.org/pdf/2307.16892

[6] https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.16802

A Guide to Gasification - How Gasification Is Paving the Way for Sustainability

By Brad Price.

New Energy Risk helps accelerate the commercialization of industrial technologies that are solving global challenges. One of the technology platforms which we frequently review is gasification. This important process contributes to the production of low-carbon fuels and the development of a more circular economy, and we are proud to help our clients bring it to commercial scale.

What is Gasification?

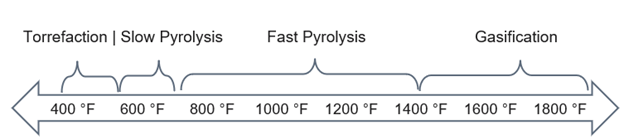

Gasification is a natural topic to follow my last blog post, A Primer on Pyrolysis, since it is the next step on the scale of thermal deconstruction chemical processes, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – General temperature ranges of thermal deconstruction chemistries

Gasification is a process of partial oxidation (think partial combustion) that occurs above about 1400 °F (760 °C). It is used to convert a solid feedstock (like coal or biomass) or a liquid feedstock (like petroleum products), into synthesis gas (otherwise known as ‘syngas’). The key source of oxygen for the partial oxidation is usually either air, purified oxygen, or steam (via the “O” in H2O). The amount of oxygen supplied is significantly less than is required to completely burn the feedstock. Synthesis gas is primarily composed of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), and methane (CH4). 'Synthesis' (or 'synthetic') is in contrast to 'natural' gas, which is naturally occurring. Syngas and was historically produced from coal before petroleum-based natural gas was available.

Whereas pyrolysis results in a partial deconstruction of the feedstock, gasification can be considered a near-complete destruction of the feedstock into its most basic building blocks. It utilizes the brute force of intense heat and oxygen to break nearly all the chemical bonds in the feedstock; few other chemical processes operate at a higher temperature.

When fed with biomass feedstock, the gasification process can produce renewable, low-carbon fuels, chemicals, and various other products. Using biomass (like wood, grass, or other organic matter) as a fuel source is considered low-carbon and renewable because the carbon emitted during the combustion process is offset by the carbon that the plants absorb during their lifetime through photosynthesis. This carbon is normally returned to the atmosphere as CO2 during the natural decomposition process (i.e., rotting). This carbon is instead returned to the atmosphere when the gasification products are burned as fuel, doing useful work, and since the next generation of plants will absorb the same amount of carbon it creates a closed carbon cycle.

Another beneficial way to use gasification is when a waste stream is used as a feedstock, such as plastic waste, municipal solid waste (trash), or wastewater treatment sludge. Gasification can give new life to these materials. By using waste as a feedstock, gasification helps to reduce the amount of waste sent to landfills or incinerators, which can help to decrease greenhouse gas emissions and environmental pollution. Additionally, gasification can provide a local source of energy and reduce the reliance on fossil fuels, thereby contributing to energy security and promoting sustainable development. Overall, the use of waste in gasification allows for a more ‘circular’ economic system, where waste is repurposed and/or reused, rather than a straight-line path from production to disposal. This approach can help to reduce waste, conserve resources, and promote a more sustainable, circular economy.

Is Gasification New?

Far from it – gasification has a long history. As early as the 1820’s, the streetlights in England were fueled using synthesis gas (also known as “town gas”) from coal gasification plants. They were referred to as “coal distillation” plants and were operated to maximize the production of liquid tars; an important precursor to the burgeoning fabric dye industry (1). It is difficult to overstate the impact of this gaseous fuel byproduct of coal distillation on the day-to-day life of those who were able to access it because it was cleaner and more practical than other energy sources. Synthesis gas played a key role in the energy mix in the UK until the 1970’s, during which period 13 million homes were transitioned from synthesis gas to natural gas (2) This transition was a monumental undertaking that required the conversion or replacement of each and every town gas fueled appliance. It is fair to say that gasification and synthesis gas played a significant role in the industrial revolution.

Far from it – gasification has a long history. As early as the 1820’s, the streetlights in England were fueled using synthesis gas (also known as “town gas”) from coal gasification plants. They were referred to as “coal distillation” plants and were operated to maximize the production of liquid tars; an important precursor to the burgeoning fabric dye industry (1). It is difficult to overstate the impact of this gaseous fuel byproduct of coal distillation on the day-to-day life of those who were able to access it because it was cleaner and more practical than other energy sources. Synthesis gas played a key role in the energy mix in the UK until the 1970’s, during which period 13 million homes were transitioned from synthesis gas to natural gas (2) This transition was a monumental undertaking that required the conversion or replacement of each and every town gas fueled appliance. It is fair to say that gasification and synthesis gas played a significant role in the industrial revolution.

While gasification is not new, in many places it has been replaced by other more efficient fuel sources like natural gas. The story in the UK was repeated around the world as natural gas presented a much more energy dense alternative to synthesis gas as a fuel, and much less toxic due to the lower content of carbon monoxide. Despite this, it has never quite gone away.

A modern example of gasification is China’s chemicals industry. China has built an extensive chemicals and fuels industry on a foundation of coal gasification. While China is limited in its petroleum resources, its coal resources are vast. The National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) has documented over 100,000 ton/day of aggregate capacity for coal gasification in China, with over 70,000 ton/day capacity under construction (as of 2014). This capacity is used to produce base chemicals and products such as ammonia, methanol, synthetic natural gas, hydrogen, liquid fuels, DME, olefins, and plastics (3).

What Does Gasification Produce?

As mentioned earlier, gasification primarily produces a synthesis gas composed of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), and methane (CH4). Generally, however, this is not the final product or purpose of a gasification plant. The “magic” of syngas is the fact that it can be converted into so many different useful products.

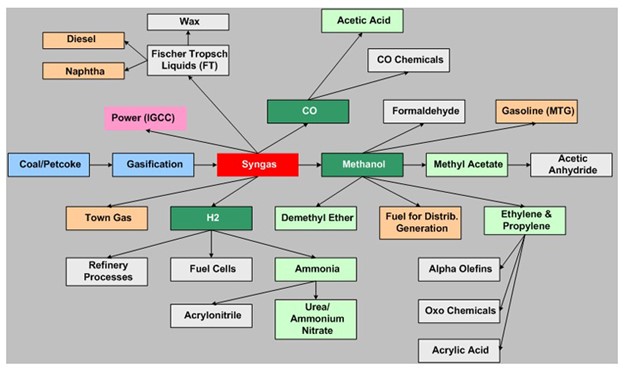

Figure 2 below shows many of the different product pathways from a gasification plant. In addition to power, these include naphtha and diesel produced via Fischer-Tropsch Liquids, methanol, ethylene and propylene, hydrogen, ammonia, and many other products. As a result of these numerous pathways, gasification can be viewed as an alternative way of producing virtually every chemical that can be produced from petroleum-based feedstocks.

In addition to syngas, gasification produces small quantities of tars. “Tar” has a long history in the development of Organic Chemistry in the 1800s but has generally been poorly defined and is less important today. It is a mixture of high-viscosity aromatic compounds that can foul downstream equipment if not properly accounted for.

There can also be a carbon or coke product from gasification. This can be thought of as charcoal, although its properties can be somewhat different. The amount of coke produced depends greatly on the operating conditions and the feedstock composition.

Another undesirable byproduct of gasification is ash. Ashes are created due to contaminants in the feedstock that cannot be gasified, such as metallic and salt impurities. Depending on the operating temperature of the gasifier and the composition of the ash, this ash can melt or “slag.” Controlling the slagging conditions is important in all gasifiers.

Figure 2 – Chemical pathways from gasification (4)

What is New in the Story of Gasification?

Much like pyrolysis, recent innovation in gasification is related to feedstock. While coal has been industrially gasified for over 200 years, there are many feedstocks that had never been successfully gasified at scale until recently.

A perfect example of this is Fulcrum BioEnergy. Their Sierra BioFuels Plant gasifies municipal solid waste to produce syngas, which is then liquified using Fischer Tropsch technology to produce synthetic crude oil. Producing synthetic crude oil by gasification of municipal solid waste had never been done at scale before this facility. New Energy Risk partnered with Fulcrum Bioenergy in 2017 by providing a customized technology insurance solution to increase project attractiveness to investors (5). Fulcrum announced that in December 2022 the Sierra site had produced its first barrels of synthetic crude. (6)

In addition to municipal solid waste, many other feedstocks are being considered for gasification, including agricultural wastes and byproducts, wood, sewage sludge, and food production byproducts.

What Is the Business Case for Gasification Today?

Gasification is always an upgrading process, meaning it transforms lower priced feedstocks into higher value products. The products are generally commodity base chemicals or fuels. Since base chemicals all have the same product qualities, a competitive advantage cannot be obtained on the product side. As one might expect then, competitive advantage in gasification is related to the feedstock. Gasification’s business case is strongest when there is a financial advantage due to either a low-cost feedstock or a feedstock that is renewable or recycled, providing additional value to the products. Gasification represents a key pathway to low-carbon fuels and recycled materials.

Many of the business models New Energy Risk has seen are built around biomass as a feedstock for gasification. The material may be low-cost waste streams from other industrial or agricultural processes. The target products qualify for biofuel credits that then receive a Renewable Identification Number (RIN) and/or qualify for the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) credits, which can be extremely lucrative, especially when used in transportation applications.

An advantage of gasification is that it tends to be able to handle feedstocks that are more contaminated (“dirtier”) and therefore less expensive to procure. This reiterates the importance of feedstock on the business model because a low-cost, contaminant-heavy feedstock is the ideal case for a successful gasification business model that can compete with other technologies.

Figure 3 - Gasifier types Source: Wikipedia

Another advantage is on the product side. As shown in Figure 2, gasification can be a precursor to many different chemical products. This flexibility tends to surpass any other chemical process. For example, pyrolysis only yields a crude-oil like product and requires further processing into higher-value products. This allows the gasification business model to be built around a low-cost or advantaged feedstock on the front end and pick from a wide range of products on the back end to maximize the total value created by the asset.

What Are the Challenges for Gasification?

Nothing is easy about innovation. To design a reliable (and profitable) process, technology developers must identify and mitigate many issues that are unique to each technology. Unfortunately, innovative technology projects frequently fail. Even with proper piloting, innovative process technologies on average only achieve ~80% of the design production rate six months after startup. Without proper piloting, this number is closer to 50%. (7)

The first challenge area for gasification is solids handling. Solids handling can be the bane of an innovator’s existence. While mundane, it oftentimes causes significant reliability issues. The feedstock and the coke and the ash byproducts are oftentimes sticky or otherwise difficult to convey and can cause mechanical problems due to buildup on the inside of the equipment. The equipment tends to require additional maintenance when compared with equipment in liquid or gas service. Spare equipment is oftentimes required to handle the outage time associated with these activities.

Tar formation represents a challenge to all gasification processes. When cooled, this material can polymerize and deposit on downstream equipment, resulting in significant plugging of equipment and downtime to clean it. Technologies exist that destroy these tars at extremely high temperatures, or chemically react them to more stable components. Every gasification plant needs to have a plan that has been field tested to handle these compounds.

Slagging is an issue for both slagging and non-slagging gasifiers. For slagging gasifiers, the ash needs to melt. This will require monitoring of the melting point and potentially adding material that ensures all the ash melts and ends up in the slag stream. These are some of the hottest gasifiers available, resulting in more technology risk because of these severe conditions. For non-slagging gasifiers, the ash needs to be monitored to ensure that it does not melt. For example, in a non-slagging fluidized bed gasifier, if the ash starts to melt, the entire fluidized bed can collapse, and then require a jackhammer to remove the agglomerated bed material from the gasifier. The feedstock is the primary determining factor of the ash melting point, so it is important for developers to fully understand the melting point of the ash in their feedstock.

How Can New Energy Risk Help with Your Gasification Process?

Financing an innovative gasification process can be a challenge, due to the risks associated with innovative technology. NER is positioned to provide performance insurance solutions to protect capital providers if the technology does not perform as expected. NER’s in-depth diligence process and innovative technoeconomic modeling allows us to quantify the risk associated with projects deploying these technologies. We have over a decade of experience enabling developers to de-risk their project and attract capital at terms that are impossible to achieve without insurance.

An example gasification client of ours is Fulcrum. NER was able to assist Fulcrum by helping to provide a performance insurance solution to protect bondholders in their project debt financing. In 2017, Fulcrum was able to secure $175 million in debt capital (bonds), and NER’s insurance product helped to improve the interest rate on those bonds by 2% annually. Construction at the site has completed, and the Fulcrum team announced in December 2022 that the site had begun production of their synthetic crude oil. (6)

Gasification is just one example of the innovative technologies that we evaluate and support at NER. This is part two in our series that takes a closer look at some of these innovations. Next up: A Teaser on Torrefaction.

Works Cited

[1] Aftalion, Fred. A History of the International Chemical Industry. Philadelphia : Chemical Heritage Foundation, 2001.

[2] Office for Budget Responsibility. Decarbonising domestic heating: lessons from teh switch to natural gas. [Online] July 2021. [Cited: March 13, 2023.] https://obr.uk/box/decarbonising-domestic-heating-lessons-from-the-switch-to-natural-gas/.

[3] Nathonal Energy Technology Laboratory. China Gasification Database. [Online] July 2014. [Cited: March 14, 2023.] https://netl.doe.gov/research/coal/energy-systems/gasification/gasification-plant-databases/china-gasification-database.

[4] Nathional Energy Technology Laboratory. 12.1. Overview: Chemicals From Gasification. [Online] [Cited: March 14, 2023.] https://netl.doe.gov/research/carbon-management/energy-systems/gasification/gasifipedia/chemicals.

[5] New Energy Risk. Case Studies. [Online] [Cited: March 14, 2023.] https://newenergyrisk.com/case-studies/.

[6] Fulcrum Bioenergy. Fulcrum Bioenergy Successfully Produces First Ever Low-Carbon Fuel from Landfill waste at its Sierra BioFuels Plant. News and Resources. [Online] December 20, 2022. [Cited: March 14, 2023.] https://www.fulcrum-bioenergy.com/news-resources/first-fuel-2-2.

[7] Andras Marton, Ph.D. Getting Off on the Right Foot - Innovative Projects. Independent Project Analysis Newsletter. March 2011, Vol. 3, 1.

The Evolving Advanced Recycling Supply Chain - The Importance of an Industry Feed Specification

By Krista Sutton.

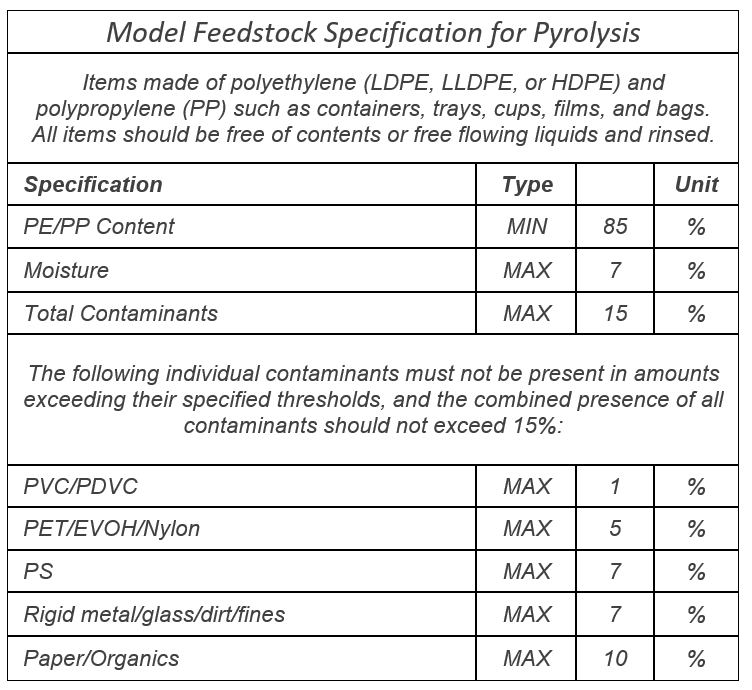

New Energy Risk helps accelerate the commercialization of industrial technologies that are solving global challenges. One of the technology platforms that we see increasingly is pyrolysis technology being deployed in the development of a more circular plastic economy. A key challenge for those developing these projects is securing a bankable feedstock agreement for waste plastic. This challenge is magnified by the fact that the industry has not developed a standardized feedstock specification for pyrolysis of waste plastic.

The Big Picture

Increasing awareness of the extent of plastic pollution and the focus on sustainability are creating demand for recycled material in consumer products. The market incentives are growing and come from many different sources including consumer preferences and a willingness to pay a premium for recycled products, plastic taxes, corporate pledges, recycling mandates, single use plastic bans or taxes, extended producer responsibility programs, upsets in the global supply chain following China’s national sword policy [8], subsidized local recycling programs, and increased landfill fees to name a few.

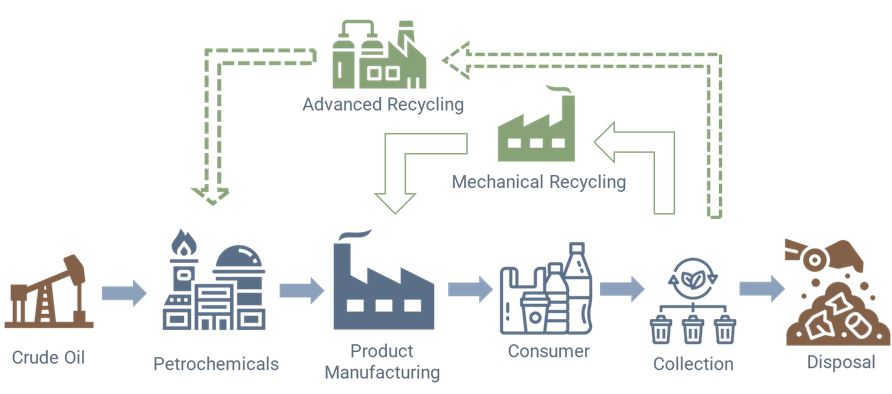

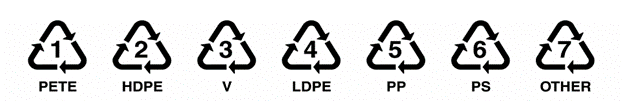

Today the recycling value chain largely consists of mechanically recycling (sorting, shredding, washing, drying, grinding, melting, granulating, and compounding) diverse plastic streams to produce recycled granules that can replace virgin plastic granules in the manufacturing of some plastic products, notably not always the same plastic products that the recycled products came from as there are stringent restrictions on products like food grade packaging.