Interview: Vinita Jajware-Beatty, Enkompass

Interview: Vinita Jajware-Beatty, Enkompass

We are inspired by people who are passionate about insurance, project finance, and technology that solves pressing global challenges. In this interview series, our chief actuary, Sherry Huang, talks with friends of New Energy Risk whose work makes a difference, and whose journeys will inspire you, too.

I first met Vinita Jajware-Beatty at the Women In Insurance Tech Conference in 2022. She was the chairperson of the conference, partnering with the organizer (Altaworld) and representing the Toronto Insurance Women’s Association (TIWA) as its president. The conference included a wide range of topics on innovative technologies serving the insurance industry. Vinita was the best MC I have ever met at any conference. She was knowledgeable, engaged, and authentic, reading the room and connecting the dots between different segments of the insurance industries, technology vendors, as well as current trends.

I first met Vinita Jajware-Beatty at the Women In Insurance Tech Conference in 2022. She was the chairperson of the conference, partnering with the organizer (Altaworld) and representing the Toronto Insurance Women’s Association (TIWA) as its president. The conference included a wide range of topics on innovative technologies serving the insurance industry. Vinita was the best MC I have ever met at any conference. She was knowledgeable, engaged, and authentic, reading the room and connecting the dots between different segments of the insurance industries, technology vendors, as well as current trends.

I spoke to Vinita afterwards and found out she has a diverse background that combines engineering risk assessment and various related insurance applications. Vinita is currently the Chief Operating Officer of Enkompass Power & Energy Corporation, a national engineering and field services firm, Enkompass has operations rooted in industries including construction; telecommunications; healthcare; manufacturing; food and beverage; pharmaceutical; mining; and insurance.

Vinita is responsible for operational oversight of engineering and field services including Enterprise Risk Management and Human Resources, while maintaining a loss control engineering and commissioning professional practice. In addition to her leadership roles at Enkompass, TIWA and Altaworld, Vinita also serves as Chair of Dive In in Canada, a Diversity, Equality and Inclusion (DEI) initiative from Lloyds of London.

After our meeting, we are excited to find out more about each other’s work as we both operate on the intersection of engineering and insurance. I am also intrigued by her drive for excellence and sense of purpose in moving DEI forward.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Please tell us a little about how you got to where you are today.

Through grit, hard work, and perseverance. I was fortunate to have excellent mentors and career champions along my journey but even with those resources it did not replace the hard work needed along the way.

You are the best MC I have ever met! What foundations provided you with the building blocks for your communications skills?

Thank you for the kind words! I was fortunate that, at a young age, I was able to hone my public speaking skills through extracurricular activities in student leadership going back to my early high school days. Through my work with the Toronto South Asian Film Festival (Filmi) and starting a not-for-profit organization within the student leadership space, I was able to hone both my public speaking and media facing experience.

How do engineers and insurance professionals view risk differently?

Insurance professionals tend to think in absolute terms with very little grey area and this is often reflected in traditional insurance policies. Engineers are trained, regulated professionals who manage risk by nature of their profession, typically dealing with one or more constraints at the same time, while attempting to solve a problem. As the engineering profession is regulated around public safety and welfare, this places the onus of risk mitigation as paramount in the professional’s practice. Some creative insurance professionals also view risk in the same lens and ensure their policies are treated the same way.

Has there been a mentor(s) in your life who changed the trajectory of your career path?

I am very fortunate to have had many mentors over the last fifteen years of my career. These individuals include clients, senior engineering colleagues, and the insurance executives and professionals that I am privileged to work with on DEI initiatives. I would be remiss if I did not mention Professor Helmut Brosz and Steve Paniri, two senior electrical forensic engineers who were instrumental in providing me with a strong technical foundation, as well as Eileen Greene with HKMB HUB International for her guidance, mentorship, and support over the years.

What is your leadership style?

Based on conventional leadership archetypes, I definitely identify as a Servant Leader. In today’s knowledge-based workforce that can be an advantage toward motivating teams to reach their goals and objectives. At the same time, I am also an empath and that can be a challenge to compartmentalize the issues within a team and not have that affect me personally.

What does success mean to you?

Being able to live wisely, agreeably, and well by knowing my personal values, morals, mission, and vision is aligned with the work that I do. Having the freedom to pursue projects and initiatives that align with those values and general purpose is how I define success, as well as the means to support the goals of my family.

Interview: Denise Olson, Zurich

We are inspired by people who are passionate about insurance, project finance, and technology that solves pressing global challenges. In this interview series, our chief actuary, Sherry Huang, talks with friends of New Energy Risk whose work makes a difference, and whose journeys will inspire you, too.

Denise Olson is the head of programs at Zurich North America. I reached out to her earlier this summer to ask her about her career transition from an actuary to an underwriter and business executive. She is genuine, approachable, and has a deep passion for insurance coverages and for her team at Zurich. Since joining Zurich in 2003, Denise has been an active ambassador of Zurich’s innovative programs and initiatives. In addition to several leadership roles she held in underwriting, product management and actuarial, she was also named a Zurich KAMP (Keeping A Meaningful Perspective) Leadership Award honoree in 2020.

(For readers who might not be familiar with program business, it is a grouping of insurance customers with common operations, such as wineries, golf courses, and manufacturers, to name a few. The management of program business often involves an intermediary that assumes many of the roles of an insurance company. This is achieved through the delegated authority of an established insurance company, which allows the intermediary to market and sell policies under its own brand.)

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Denise, congratulations on your recent promotion to the head of programs at Zurich. Please tell us a little about how you got to where you are today.

I actually intended to get into insurance from the beginning. When I was a junior in high school, I went to my math teacher to ask about what I could do with a math major apart from being a math teacher. She told me about actuarial science as a major and being an actuary as a career, and my path was sealed then. I went to University of Nebraska, which was close to my hometown, and studied Actuarial Science.

I started my career in CNA’s property and casualty department as a pricing actuarial analyst. This was a tremendous place to grow my career thanks to its rotation program. I had exposure to a broad range of pricing assignments and rose to a leadership role during the 12 years I was there. A few years after joining Zurich, I moved into an underwriting manager role overseeing the commercial auto program, which was a little daunting initially, but I thought, if it didn’t work out, I could always go back to pricing. I got my Chartered Property Casualty Underwriter designation during the first year of my transition, which was one of the best things I’ve done in my career, and I learned that I love insurance coverage.

I applied and got my next role as the head of product development, which was a great responsibility that involved a lot of project management and change management. This experience led me to my current role as the head of new programs for Middle Market at Zurich and, eventually, to the head of programs.

Do you have any mentors who helped guide your career?

Yes, I had many, and some of them I didn’t recognize as my mentors until later. The most significant mentor I have is Greg Massey, who recently retired from Zurich. He was my biggest career champion; I wouldn’t be where I am today without him. Greg was really good at providing immediate feedback, and he saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself. Kyle Nieman from my CNA days was another mentor; he allowed me to work part time from home when I had a young family and, as a result, provided the work-life balance I desperately needed to succeed. This is common practice now but unheard of back then, especially since I was a people manager. I learned from Kyle the value of creating a tailored solution for each situation and appreciate him still today for going above and beyond for me.

What are you looking forward to accomplishing in your current role?

I am looking forward to developing talents and creating a strong succession plan within my team. I want to continue to spark curiosity and create passion by learning the unique perspectives of the individuals I work with. I want to leave the team better than when I found it. I am also looking forward to continuing to advocate for women and make sure diversity and equity are considered in our operations. This is important both to me and to Zurich as a whole.

I have been inspired by how outspoken and supportive Zurich's CEO, Mario Greco, is about social issues, and how ambassadors like you help promote and live those core values. Are there any specific employee programs at Zurich that you would like to highlight?

Zurich has a strong program with its Employee Resource Groups. It includes groups like Women’s Innovation Network, ABILITIEZ (for disabled individuals), VETZ (for veterans) and PRIDEZ (for the LGBTQ employee communities), among others, and each affinity-based group is sponsored by an executive. During the pandemic especially, it was a lifeline for many, including myself, as it allowed me to connect with my colleagues in a safe, healing space.

Zurich’s Apprenticeship Program is another wonderful resource that provides a career path for young people who have the aptitude but not the typical opportunity. During a two-year commitment, apprentices are paid a full-time salary to work part time at Zurich while also earning an associate’s degree at a local college. Completion of the two-year commitment brings guaranteed job placement. This has been a successful way to grow talent in the insurance industry and foster diversity in our workforce.

What suggestions do you have for program administrators working with various carriers’ program businesses?

In addition to being the great underwriters you are, invest in data and technology platforms. Make sure you capture and obtain data with the required granularity (buy third-party data, if necessary), and invest in the talent to be able to process and understand the data. Invest in a technology platform, as that is the way to stay ahead of the competition.

If you were no longer working, what else would you enjoy doing?

I love to golf and can imagine myself spending a lot of time golfing when I am no longer working. I also love to cook, and I would open a bed and breakfast serving afternoon appetizers and fresh food from my garden.

Thank you, Denise! We hope to visit you in that well-deserved B&B someday!

###

Opponents Of Joe Manchin’s Permitting Reform Demonstrate Why We Need Permitting Reform

By Brentan Alexander, PhD, President

Less than one week ago, Senators Joe Manchin and Chuck Schumer shocked Democrats and Republicans alike with their announcement of a reconciliation package that included significant climate and energy provisions: the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Although much reporting has been focused on the specifics of that package, Manchin conditioned his support on Democratic leadership taking up environmental permitting reform in a separate bill later this session. Last week, Manchin released a 1-page summary of his proposed permitting reform bill, outlining the reforms he seeks and the benefits it will provide to clean and fossil technologies alike. Environmental groups were quick to jump on the proposal as an ‘attack,’ singling out the fossil provisions in particular. Although the proposed reforms are not perfect, there should be no doubt that broad-based permitting reform is needed to advance the clean agenda, and this bill is our best chance to get it. Without it, the tactics pioneered by the environmental movement will continue to be used to subvert the clean infrastructure of tomorrow.

The environmental movement has been incredibly successful over the last half-century at advancing legislation and policies that restrict project development through the careful review of environmental impacts. A landmark 1970s law, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), requires project developers across a range of industries to tally and mitigate impacts on air, water, noise, traffic, and more.

Fifty years in, NEPA has stopped countless environmentally destructive projects from breaking ground and has significantly slowed the process through which new projects get permitted and built. NEPA, however, has also shown itself to be vulnerable to abuse. The law fails to provide guidance for how to balance the trade-offs inherent in any development, and the qualitative nature of many environmental impacts, combined with the sheer number of impacts that must be mitigated, invites lawsuits and challenges. Opposition groups can readily contend that a project has not properly accounted for its impacts or that the project benefits have been overstated. Lawsuits challenging project reviews can tie up a developer in costly litigation for years, effectively killing projects.

The result has been a perversion of the law’s original intention and a weaponization of NEPA from groups on both sides of the aisle. Proposals from bike lanes to enrollment increases at UC Berkeley have been knocked off-course by bad-faith uses of NEPA. The law, designed to prevent bad projects from getting built, instead is preventing any project from getting built. It has become a defender of the status-quo, which is a problem when the status-quo is destroying the planet.

Surprisingly, it’s often the very environmental groups cheering clean energy investments who wield NEPA lawsuits against clean energy infrastructure. The fundamental problem is that any technology has environmental and social impacts of one form or another. A project that sucks CO2 from the air can incentivize the continued operation of a fossil-fired facility in underrepresented communities. Nuclear facilities produce long-lasting radioactive waste. There is no silver bullet to the climate and environmental justice crises; no one technology or solution will satisfy every audience. For example, just two months ago, 73 groups penned a letter to California Governor Gavin Newsom outlining their opposition to the widespread adoption of a variety of clean technologies, including renewable fuels, carbon capture from power plants and other industrial facilities, and direct-air capture. The reality is that most projects will find themselves with at least one group in opposition, and only a single opposition group is needed to weaponize NEPA and derail a project.

Without reform, abuses will continue and good projects will be killed. Even when the Inflation Reduction Act becomes law, the incredible investment in clean and renewable technologies it will enable will only bear fruit if projects that make actual impacts are built. Manchin’s goal of tying energy investment with environmental permitting reform is good policy: Neither reform is likely to be successful without the other.

###

A Primer on Pyrolysis

By Brad Price, P.E.

New Energy Risk helps accelerate the commercialization of industrial technologies that are solving global challenges. One of the technology platforms that we review frequently is pyrolysis. This important process contributes to a circular economy, and we are proud to help our clients bring it to commercial scale. This is Part 1 in our series that takes a closer look at innovations changing our world.

What is Pyrolysis?

A Dictionary of Chemistry defines pyrolysis simply as "chemical decomposition occurring as a result of high temperature." (1) In practice, pyrolysis technology is a family of technologies based on pyrolysis chemistry. Pyrolysis chemistry is simply what happens to a material (in solid, liquid, or gaseous state) when it is heated in the absence of oxygen. Molecules start to “crack” when heated to high temperatures, which means they start to spontaneously break apart and recombine in random and yet somewhat predictable ways. No additional ingredients like catalysts or initiators are required, although they can enhance the process. Pyrolysis is used to upgrade a lower value material into a higher value material; depending on the feedstock, it is sometimes referred to as a “waste to value” process.

Is Pyrolysis New?

Not at all! Pyrolysis chemistry is core to several of the largest and most important industrial processes in the world.

A great example is ethylene. Ethylene is produced using pyrolysis chemistry and is considered the world’s most important chemical as it is needed for the production of products as diverse as industrial chemicals, specialty glass, metals, food, medical anesthetics, refrigerants, rubber, and much more. (2) It is forecast that ethylene production will be 202.9 million metric tons by 2026, more than any other organic chemical. (3) Ethylene is made from a variety of hydrocarbon feedstocks (e.g., ethane, propane, naphtha) primarily using steam cracking furnaces. These furnaces are giant, fired tubular reactors that operate in the range of 1400 to 1600 °F (~750 to ~875 °C), with a gas residence time of 0.1 to 0.5 seconds to complete the conversion! (4)

Examples of pyrolysis products and technologies include pyrolyzing wood to produce one of America’s favorite backyard barbecue fuels: charcoal. [1] In an oil refinery, one of the largest and most visible units is the coker unit, which also utilizes pyrolysis chemistry. [2]

What is New About Pyrolysis?

There is tremendous change happening with pyrolysis. Generally, feedstock is the key focus area NER has seen innovating. There are many feedstocks that had never been used successfully at commercial scale in a pyrolysis process but that are coming to fruition today.

An example of a new feedstock is waste plastic. Many innovators are attempting to commercialize waste plastic pyrolysis processes to produce liquids and gases that are then used to produce new “virgin quality” plastic. These output plastics, which have been “chemically recycled,” are molecularly identical to regular plastic and have advantages over more traditional “mechanically recycled” plastic in that there is no compromise on the material properties of the plastic. I have witnessed this process firsthand because I was part of my previous company’s first successful commercial trials to process waste plastic pyrolysis oil through steam cracking furnaces to produce ethylene.

Pyrolysis is also being applied to biomass feedstocks made from residual agricultural wastes, for example. The liquids produced from biomass ultimately qualify as biofuels and can be extremely attractive to customers looking for a more carbon-conscious fuel. Pyrolysis oil from biomass has very different properties than the oil produced from waste plastic, and has different properties depending on the biomass material being pyrolyzed. These properties do not allow the pyrolyzed oil to be used directly as a transportation fuel; this is a challenge that has and will continue to require significant innovation.

What Does Pyrolysis Produce?

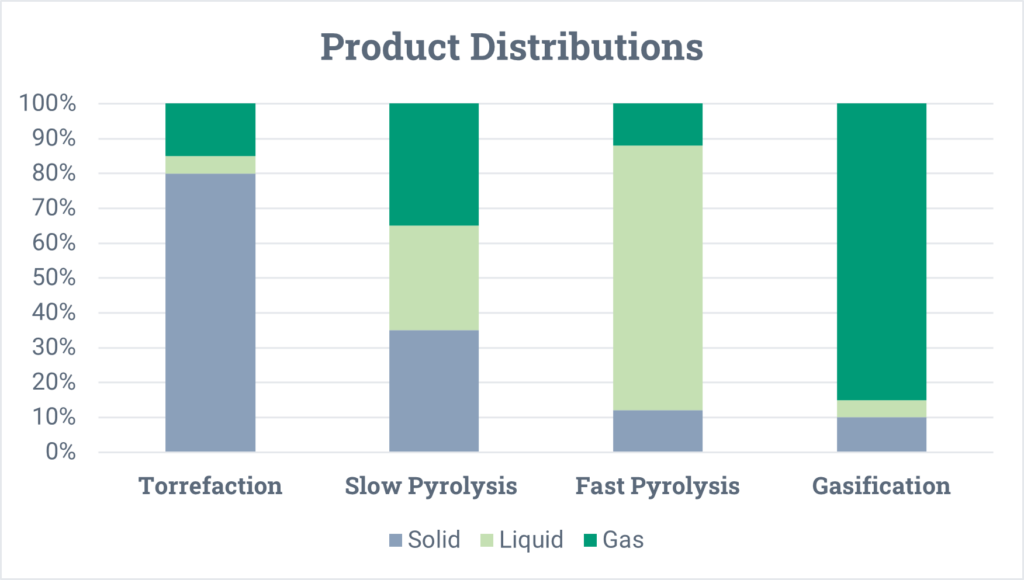

In general, pyrolysis produces three products: a solid, a liquid, and a gas. The ratios of these three products depends primarily on the reaction temperature and the feedstock being processed.

- The solid is oftentimes referred to as coke or char. It is carbonaceous and has a similar appearance to coal or black powder. Depending on the properties of this material, it can have many uses, such as for carbon black (for pigmentation and tire rubber strengthening), for soil enhancing, or as a fuel source.

- The liquid is a broad boiling range product, like crude oil. The oil has distinct properties that make it very different from fossil crude oil, and those properties depend on the material being pyrolyzed and the operating conditions (temperature, pressure, and residence time) of the pyrolysis reactor. Generally, this liquid must go through several upgrading processes prior to being used as a transportation fuel or a chemical intermediate (as is also true for fossil crude oil).

- The gas product is non-condensable and goes by many names such as syngas or cracked gas. Common molecules found in this gas include hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, ethylene, and propylene. This gas can be recovered for fuel or sold as a chemical feedstock to other industrial processes.

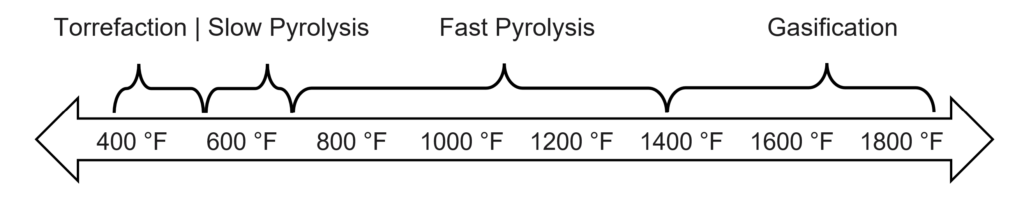

Pyrolysis falls on a spectrum of similar thermal deconstruction chemical processes, including torrefaction, slow pyrolysis, fast pyrolysis, and gasification. They are shown below, organized by the temperature ranges they typically fall in.

The product distributions for each of these categories are shown below. Keep in mind that these are very generalized and can vary significantly depending on the feedstock, operating temperature, pressure, and residence time of the feedstock in the reactor.

What Is the Business Case for Pyrolysis?

Pyrolysis is always an upgrading process, meaning it transforms lower priced feedstocks into higher value products. The products are generally base chemicals or fuels and not as highly valued as specialty chemicals (there are exceptions). The business advantage of pyrolysis is usually related to feedstock. A low cost or otherwise strategic feedstock is where pyrolysis really shines.

For example, waste plastic feedstock is generally low cost, and may even result in the processor receiving tipping fees (getting paid to take feedstock!). In addition, the product can be certified as recycled material, which demands a premium in the marketplace. When the recycled pyrolysis products are then used to produce new plastic, that plastic product can be certified as recycled, or circular, too.

Similar business cases exist for biomass as a feedstock for pyrolysis. The material may be low-cost waste streams from other industrial or agricultural processes. The resulting liquid then qualifies for biofuel credits that then receive a Renewable Identification Number (RIN) and/or qualify for the Low Carbon Fuel Standard credits, which can be extremely lucrative.

What Are the Challenges for Pyrolysis?

Innovation in the process industry is challenging. To design a reliable (and profitable) process, technology developers must identify and mitigate many issues that are unique to each technology. Unfortunately, innovative technology projects frequently fail. Even with proper piloting, innovative process technologies on average only achieve ~80% of the design production rate six months after startup. Without proper piloting, this number is closer to 50%. (6)

The first challenge area for pyrolysis is solids handling. Solids handling can be the bane of an innovator’s existence. While mundane, it oftentimes causes significant reliability issues. The solid char product is oftentimes sticky or otherwise hard to convey and can cause mechanical problems due to buildup on the inside equipment. Established industry processes handle the solid byproduct by either periodically air burning it inside the reactor, or by mechanically removing it from the reactor. Spare equipment is oftentimes required to handle the outage time associated with these activities.

Product quality is another challenging area for pyrolysis innovators. The liquids and gasses produced can be very different from produced by typical fossil-derived processes, and it may be difficult to find customers that are able to receive such a feedstock product. These feedstocks can be full of contaminants, and the resulting product can be acidic and unstable. Many customers will require significant quantities of product to test it, qualify it, and establish contractual acceptance criteria. Upgrading of the liquids can be equally challenging and requires significant development work to ensure the upgrading equipment is compatible with the properties of those liquids.

How Can New Energy Risk Help with Your Pyrolysis Process?

Financing an innovative pyrolysis process can be a challenge, due to the risks associated with innovative technology. NER is positioned to provide performance insurance solutions to protect capital providers if the technology does not perform as expected. NER’s in-depth diligence process and innovative technoeconomic modeling allows us to quantify the risk associated with projects deploying these technologies. We have over a decade of experience enabling developers to de-risk their project and attract capital at terms that are impossible to achieve without insurance.

An example pyrolysis client of ours is Brightmark, which is currently finishing construction of their flagship waste plastic pyrolysis facility in Ashley, Indiana. NER was able to assist Brightmark by helping to provide a performance insurance solution to protect bondholders in their project debt financing. In 2019, Brightmark was able to secure $185 million in debt capital (bonds) at a low 7.125% interest rate, in part due to NER’s insurance solution.

Pyrolysis is just one example of the innovative technologies that we evaluate and support at NER. This is Part 1 in our series that takes a closer look at some of these innovations. Next up: A Guide to Gasification.

[1] The ubiquitous backyard grilling product we call charcoal is produced using pyrolysis chemistry. Modern production of charcoal is not much different from how it was produced anciently and requires temperatures around 750 °F (~400 °C).

[2] The global refinery coking capacity is around 9,603 million barrels per day (8). These massive units upgrade some of the heaviest oils in a refinery into gasoline, diesel, and other more valuable fuels using pyrolysis chemistry. They operate at temperatures around 900 °F (~500 °C).

Works Cited

- Daintith, John, [ed.]. A Dictionary of Chemistry. Sixth. Oxford/New York : Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Kaskey, Jack. Harvey Has Made the World’s Most Important Chemical a Rare Commodity. Bloomberg. [Online] August 31, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-01/world-s-most-important-chemical-made-rare-commodity-by-harvey.

- Research and Markets. Global Ethylene Production Capacity & Demand Markets, 2022-2026: Rising Production Capacity of Ethylene Dichloride, Growing Petrochemical Industry, & Increasing Demand for Bio-based Polyethylene. Cision PR Newswire. [Online] February 07, 2022. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-ethylene-production-capacity--demand-markets-2022-2026-rising-production-capacity-of-ethylene-dichloride-growing-petrochemical-industry--increasing-demand-for-bio-based-polyethylene-301476354.html.

- Murzin, Dmitry Yu. Chemical Reaction Technology. Berlin/Boston : Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2015.

- Lindstrom, Jake K, et al. Condensed Phase Reactions During Thermal Deconstruction. [ed.] Robert C. Brown. Thermochemical Processing of Biomass. Second. Chichester : John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2019.

- Andras Marton, Ph.D. Getting Off on the Right Foot - Innovative Projects. Independent Project Analysis Newsletter. March 2011, Vol. 3, 1.

###

Interview: Kathleen Carey, Paragon

We are inspired by people who are passionate about insurance, project finance, and technology that solves pressing global challenges. In this interview series, our chief actuary, Sherry Huang, talks with friends of New Energy Risk whose work makes a difference, and whose journeys will inspire you, too.

By now, you have probably heard that New Energy Risk has been acquired by Paragon Insurance Holdings (see the press release for more details). Together, we are even better positioned to bring innovative solutions to our clients and partners while Underwriting a Greener Future. For my first interview since our new partnership, I reached out to Kathleen Carey, vice president of underwriting operations at Paragon, to learn about her journey and her work for our new owner. Kathleen is genuine, engaged, and passionate. She is also a true team player; from the start, she wanted to highlight other Paragon leaders. With such a great group of colleagues, we know NER is in good hands!

Kathleen, how did you get to where you are today? Did you ever imagine a career in insurance for yourself?

This is not intended to be a cliché response, but I got where I am through focus, hard work and self-education. (Editor’s note: Kathleen has certifications obtained through IIA CPCU, AKA the institutes, and is an active member of the Association for Insurance Compliance Professionals and currently pursuing her ACP designation.)

I didn’t set out to work in insurance. I started in computer operations (back when they had reel tapes and disk packs!). I had moved to the Hartford, CT area and applied for a second-shift operator position at Orion Capital. Instead, they offered me a different opportunity working with statistical codes for insurance policy entry into a DOS-based system. I decided to accept the job since I was newly married and preferred to work first shift. That’s how my career in insurance started!

From there, I moved through methods and procedures, underwriting, and program management, then progressed into new business coordination to assist with the operations of program launches. My career reached a pivotal point when I got involved with the launch of an alternative risk specialty program division. The program involved multiple reinsurers covering layers over primary limits on specialty ‘niche’ program business, which was a fairly new concept back in the mid- to late-90s, and what many MGAs were looking for at the time. My career progressed from there, first as the business services manager at Artis Group, director of operations for professional liability at Travelers, then vice president of operations at AIX overseeing ratings, premium audits, loss control, and compliance. At Paragon, I am now vice president of underwriting operations; I manage our support services, underwriting assistants, and premium audits.

For an audience that might not be as familiar with insurance, what’s the essence of a program business, which is Paragon's bread and butter?

Program business is niche business and unique in nature – it is not ‘cookie cutter’ insurance. For example, our contingency cancellation program provides coverage for special events, festivals, rock concerts and the like. Paragon offers underwriting expertise in these lines of business and unique coverages, so we can provide excellent service to our agent partners and maintain a solid reputation in the marketplace.

Every day here is different. We are always evolving, looking for ways to do things better, and building to stand out and be top notch.

Throughout your career, have you had any mentors who helped shape your career or inspired you? Have you ever been able to mentor someone else?

I’ve been lucky enough to have many mentors. I had a very supportive vice president of operations early in my career at Orion Capital who gave me that shot to become the new business coordinator. After I moved into underwriting, a great program manager in the transportation division took me under his wing and taught me the ins and outs of underwriting. Then there was my boss at Artis/AIX (now president at Paragon), who had confidence in me and challenged me to take on a role managing compliance, something I didn’t know much about at the time. My current manager, our COO at Paragon, has been very supportive and always listens to and values my ideas.

These invaluable mentorships helped build my own leadership style. I try to recognize people’s strengths and acknowledge their accomplishments. I have mentored many colleagues who were new to their management roles. Also, multiple people who have worked for me in the past have moved on to have successful careers. Some of them I’ve had the opportunity to recruit back onto my team again.

Tell us about Paragon’s recent and future growth and how that has influenced your day-to-day work?

Paragon is focused on solid M&A opportunities with businesses that are well established, have expertise within their staff, and fit our business model. I’ve only been with Paragon for a year and a half, and the approach has been quite successful for us even in just this time. The growth certainly influences my day-to-day work by ensuring I learn as much as I can about the new programs and work collaboratively with my team to launch the programs successfully.

Paragon has many growth opportunities ahead as we are only eight years young. Of course, I’m excited about the new business opportunities but also infrastructure growth, investment in people, service improvements, increased data reporting... all the things that will keep us at the top of our game.

What advice would you now give to yourself back when you were starting your career?

Bet on yourself; be confident in taking a chance to step into something unfamiliar and learn from it.

Thank you, Kathleen! Here's to a great NER-Paragon partnership!

###

Build Back Better Isn’t Enough: Enact Regulatory Reform to Unlock Climate Investment

By Brentan Alexander, PhD, President

Between Build Back Better, the Green New Deal, and the Infrastructure Bill, there has been no shortage of ambitious policy proposals to move the US economy towards a cleaner, more climate friendly footing. These various programs share a policy structure wherein tax incentives, grants, and other dollars are used to spur investments in climate technology and infrastructure. Investments in new research and infrastructure alone, however, won’t be enough to supercharge progress on climate because a web of regulatory approvals and permits will continue to hold back good projects. These rules, established over decades by many of the same voices that now claim an eagerness to tackle climate issues, add cost and complexity to the development and deployment of new infrastructure, hindering the very progress we need. A recent article by Alex Trembath, posted on City Journal, gives a name to this phenomenon: “cost-disease environmentalism.” A failure to address it will unnecessarily hinder the development of next-generation technology and infrastructure.

“Cost-disease environmentalism” refers to the process of enacting policy to stimulate demand, such as grants and tax incentives, without bothering to address the structural problems that inhibit supply. It is a close cousin of NIMBY-ism (“not in my backyard”), driving policymakers to advocate for money to support clean energy adoption while also supporting regulatory regimes that inhibit permitting and construction of those same clean energy projects. The most obvious culprit is the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the variety of state-level companion laws enacting its requirements. These regulations are designed to ensure new developments of all types consider the surrounding environment as part of the permitting and approval process. A noble goal for sure, but over time many have learned to weaponize these laws under the cover of ‘protecting local character’ or ‘maintaining local control’ in order to discourage or disrupt any development at all. The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), signed into law by Ronald Reagan, has been used to block everything from bike lanes to enrollment increases at UC Berkeley. Many have bemoaned the inability of the United States to build large infrastructure the way China or Europe does; the regulatory burden is a key reason why.

These laws have been a cornerstone of the environmental movement for nearly half a century and are widely viewed among environmentalists as sacred protectors of the air we breathe and water we drink. Conversations about wholesale changes to these programs are dismissed as driven by a deregulation agenda aimed at plundering the natural world. Examples of polluting projects that would have been greenlit if not for the protections these laws provide are used to justify their existence. The problem is that these laws, enacted to defend the environment, are instead routinely used to defend the status quo. Why protect the status quo when it’s playing a key role in destroying the planet?

Environmental regulation should be focused on reaching the cleaner world we seek, not freezing the world as we have it today. Projects with obvious climate merit should have a streamlined permitting and approvals path, without risk of protracted legal battles and delays. Moderate innovations in regulatory policy would lower the cost and risk of developing climate-friendly projects, driving investment and deployment without the need to spend a single taxpayer dollar.

There are examples of this working. In California, residential rooftop solar has seen explosive growth over the last decade, in part thanks to demand-side financial incentives including the federal investment tax credit and the state-level net-energy metering program. But equally significant in driving adoption were reforms on the supply-side that eased the permitting process for residential solar. California established a standard permit application for residential solar. When followed, an over-the-counter ministerial review is the only approval needed. Various laws did away with laborious planning department approvals, eliminated HOA restrictions on solar, exempted the value of the solar system from property tax adjustments, and removed the need for structural engineers, electrical engineers, and other specialists to develop and submit a permit. An expensive, multi-week process costing thousands in time and fees was replaced with a templated “standard plan” that takes under an hour to complete.

More action of this type is needed. Government tax breaks, grants, and incentives for new technologies and projects are necessary and welcome supports for the climate movement; realizing the full impact of these dollars requires coupling them with a regulatory framework that streamlines project approvals and permits for climate infrastructure.

###

Volcanic Eruptions Can Cool the Climate, But Hunga-Tonga Won’t

By Brentan Alexander, PhD, President

The eruption of the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai volcano last weekend sent a massive cloud of ash high into the atmosphere and generated a tsunami that impacted much of the Pacific Rim. As of last week, the damage from the eruption to Tonga and surrounding nations was just beginning to become known, with widespread destruction reported on the islands. Scientists have long known that large volcanic eruptions can have an immediate and years-long impact on the global climate, and an entire field of study has evolved to better understand the mechanisms. Early data from last weekend’s eruption, however, indicated it was much too small to have any meaningful impact on climate change.

One of the best known and studied volcanic events linked to a decline in global temperatures is the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines. Over the course of three days, Pinatubo released somewhere between six and 22 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, roughly equivalent to 20% of man-made SO2 released last year. Sulfate aerosols are reflective, scattering sunlight and reflecting some of it back to space. With sufficient quantities of these compounds in the atmosphere, enough light can be reflected away from earth to cool the planet.

Volcanic sulfates are especially good at impacting global climate. Man-made emissions, such as from power plants, are emitted at or near ground level and tend to remain in the atmosphere on the order of days or weeks, joining with water in the air and returning to earth as acid rain. During a massive volcanic eruption, however, much of the SO2 is lofted many miles up in to the stratosphere, above most clouds and weather, where they are only removed slowly over time through gravitational settling or large scale circulation. At that altitude, the aerosols remain for months to years. Pinatubo resulted in a global temperature decline of nearly one degree Fahrenheit during the year following its eruption.

Scientists studying this phenomenon have begun to research the purposeful release of reflective aerosols to cool the planet. So-called geoengineering would allow humankind to avoid the worst impacts of climate change by adding planet-wide cooling technology to our toolset. The technology isn’t a panacea, as even the most ardent supporters of the approach would agree. For one, sulfur compounds in the upper atmosphere have also been shown to attack the ozone layer, and much of the sulfur eventually returns to the surface as acid rain. The approach also does nothing to inhibit other environmental impacts of anthropogenic carbon emissions, such as ocean acidification. Global cooling through geoengineering or the natural volcanic equivalent is no silver-bullet for climate change. Instead, it's just one bad option in a narrowing set of tools at our disposal to avoid the worst, and scientists are working to understand the impacts and implications in case it becomes the least-bad option.

Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai, however, likely won’t serve as a test case, and won’t buy us time. Early data from Earth-observing satellites indicates that total sulfur dioxide emissions are roughly one to two percent of Pinatubo and nearly an order of magnitude too small to have any measurable climate impact. The eruption may still continue and more planet cooling gases could be released, but at this point our continued march to warmer temperatures and higher seas remains unabated. The usual solutions, from renewable energy to green hydrogen to carbon capture, remain our best tools to combat the climate crisis.

###

Interview: Sanchali Pal, Joro

We are inspired by people who are passionate about insurance, project finance, and technology that solves pressing global challenges. In this interview series, our chief actuary, Sherry Huang, talks with friends of New Energy Risk whose work makes a difference, and whose journeys will inspire you, too.

I met Sanchali Pal, CEO and founder of Joro, through our shared office space in Oakland, CA. She and her team always have a very focused look, which made me curious what they do! Joro is an application that helps people track their carbon footprint and offers ways to manage, reduce, and offset their emissions. I started using Joro myself after meeting the team behind it, and have already changed my behavior as a result. I am grateful to get to know people like Sanchali and her like-minded team who contribute to the net-zero journey with their innovative product and approach.

Sanchali, what motivated you to start Joro?

I started tracking the carbon footprint of my food consumption in college after watching the documentary Food, Inc. At the time, I was working in the dining hall and studying economics. I believed that changing the way I consumed food would have a ripple effect in the aggregate with others, that we could change demand and eventually shift how food is produced and supplied. I had a spreadsheet to track my consumption and made small but consistent changes such as eating meat less regularly.

I started tracking the carbon footprint of my food consumption in college after watching the documentary Food, Inc. At the time, I was working in the dining hall and studying economics. I believed that changing the way I consumed food would have a ripple effect in the aggregate with others, that we could change demand and eventually shift how food is produced and supplied. I had a spreadsheet to track my consumption and made small but consistent changes such as eating meat less regularly.

I continued to track my carbon footprint after college and expanded my scope beyond just food. As part of this effort, I started to bike and walk more and created an annual carbon budget for the flights I took. After graduation, I worked as a management consultant in New York, then in India and in Ethiopia. There, I witnessed firsthand the devastating effect of climate change on the poorest economies and became convinced that solving climate issues needed to be my primary focus. Meanwhile, I was still using my spreadsheet tracker. Friends and family by that point were asking me to share my tool so they could track their carbon footprints, too. Eventually, I went back to business school and then started Joro to help consumers develop a “carbon intuition” and empower people to take climate actions that matter.

Currently Joro’s platform connects with consumers’ financial activities via their credit cards. We decided to focus on providing this platform directly to consumers to provide a long-term carbon intuition at the individual level. Ultimately these same individuals are decision makers at corporations, too, so the impact ripples beyond personal choices.

What is the key challenge you are trying to solve at Joro? What’s your near-term goal for Joro?

We focused on developing the core technology over the last 18 months. We are now focusing on growth and engagement. We want to make sure the product is serving their needs in the most intuitive way. After all, the goal is to provide our customers with a tool to achieve an intuition for their actions that will have an impact. We are also working on a subscription program, where users can automatically purchase carbon offsets from our partners based on the amount of emissions their purchases generate.

How have you built your team over time? What is the key strength of your team?

The first funding we received was grant funding – from Harvard, MIT, and the State of Massachusetts. With those funds, we were able to hire undergraduate and graduate students for three semesters to help us develop the beta version of the product. Today, Joro has nine employees, including engineers, a marketer, and a designer. We’ve built our team almost entirely during the pandemic. As a team, we encompass the different personas of Joro’s users; we have diverse backgrounds and experiences, but all of us are passionate about the power of people to catalyze systems change, and we share a strong bias for action.

Have you had a key mentor in your career? Is there anyone you look up to as a role model?

I’ve had many mentors in my life, but my mom immediately comes to mind. She has been an incredible support to me and in my entrepreneurial journey, and pushes me to be confident. A CEO at a biotech start-up herself, she is passionate about her work and is an inspiration to pursue my conviction in Joro.

When I was in high school in Boston, I was intrigued when I heard on the radio about an MIT professor, Amy Smith, and her innovative solutions to fight poverty. My mom encouraged me to reach out to her, and after some resistance, I did. But she didn’t reply. So my mom suggested I follow up twice more until Professor Smith finally replied, and sure enough, I ended up with an internship at MIT the next summer. I learned from my mom to follow my passions and be persistent about pursuing them.

Another mentor who has helped me is Professor Shikhar Ghosh at Harvard Business School. His class, Founders’ Journey, focused on the human side of building a business, and gave me the guidance and inspiration I ultimately needed to start Joro.

Any advice for other founders in the technology industry? Especially for women founders?

It is really hard to be a solo female founder. I came to the Bay Area without knowing how the venture capital market works and had to overcome a steep learning curve.

I have two pieces of advice: 1. Remember your conviction – believe that the problem you identified is worth solving, and you are the perfect team to solve it. 2. Persistence is the key. It’s important to remind yourself to differentiate between the success of the company you founded versus your own success. Your company may have setbacks, but you will still have achieved a great amount with your team and as an individual.

I learned so much from talking to Sanchali. I encourage everyone to think about how you can do your part to contribute to a net-zero future. As it says on Joro’s website, “Together, we add up”!

###

The New Infrastructure Bill Looks to Solve a Clean Energy ‘Valley of Death’

By Brentan Alexander, PhD, President

Last week, the US House of Representatives finally advanced the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, capping a years-long effort to pass a variety of important domestic programs. The many provisions in the 2,740 page bill include billions of dollars in funding to support clean energy technologies and fight climate change through investments ranging from electric vehicle infrastructure to public transit. Much more is needed to avert climate catastrophe. However, there is one section of the infrastructure bill that will at least unleash numerous climate-friendly technologies: the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations.

The road from technology research and development to massive deployment at scale is long and arduous. Along the way, innovators face a number of challenges and roadblocks, so-called “valleys of death,” that must be overcome in order to achieve success. Early on, funding must be sought to advance lab-grown ideas for continued research and development. For technologies designed to fight climate change such as direct-air carbon capture and industrial green hydrogen, reaching the broader market means raising hundreds of millions of dollars from low-cost institutional capital sources for each single deployment of their technology.

Traditionally, government support programs in the US for climate-friendly infrastructure have been aimed at the valleys of death on either end of this development and commercialization pathway. Grant programs, including from the highly successful Advanced Research Projects Agency - Energy (ARPA-E), have focused on early-stage research and development. Deployment programs, such as the loan guarantees awarded by the Loan Programs Office (LPO) under the Department of Energy (DOE), have supported projects and technologies proven enough to be ready for commercial-scale deployments.

Between these stages there is a yawning gap. Innovators that have developed a working technology through research activities find themselves unable to attract the financing needed for their commercial deployments without first de-risking their technology at large scales. Therefore, climate technologies face a catch-22 at this stage in their growth: Large-scale demonstration is needed to prove technology and unlock capital, but capital is needed to fund large-scale demonstration. It’s a unique problem not faced elsewhere, including in software, where code developed in a garage can be scaled to billions of users worldwide with the press of a button. Traditional risk-capital sources, from venture capital to private equity, are poorly placed to fill the gap and fund demonstration projects due to a mismatch between their investment models, the capital intensity of clean infrastructure, and the comparatively long time horizons for returns. Whereas government programs could fill in for the private markets, those aimed at this space have been limited: ARPA-E’s SCALEUP program has deployed $75 million in total since its inception, and other programs like the $200 million investment in the Petra Nova carbon capture project were essentially one-offs.

Into this void steps the soon-to-be-formed Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations. Established under the DOE, this new office includes just under $21.5 billion in funding to be deployed over the next few years. Its formation is a significant achievement and comes with great promise. Its mandate is designed to enable the demonstration of next-generation climate technologies and position these solutions for later large-scale commercial deployment, ideally financed by private markets.

Achieving success, however, is not guaranteed. Like any government program born of compromise, the budget for this new initiative has already been allocated to specific industries and solutions: approximately $500 million for energy storage demonstrations, $2.5 billion for advanced nuclear, $3.5 billion for carbon capture, $8 billion for hydrogen, and $5 billion for the electric grid. This structure will limit the program’s ability to allocate resources to the most impactful solutions dictated by developments in technology and the marketplace. Further, the office will require DOE oversight of the execution of programs funded by the office. Oversight ensures careful stewardship of public dollars, however if taken too far it can limit the flexibility of technology developers, stifling innovations and slowing deployments.

Finally, locating this program within the DOE risks igniting bureaucratic turf wars that could undermine program objectives and exposes the office to shifts in the political climate. Run poorly, this new office could suffer the fate of LPO, which wandered in the wilderness for years after the public failure of Solyndra (though that was followed by a recent reinvigoration). Run well, the office could equal or surpass the impact of bipartisan-backed ARPA-E by funneling billions of dollars in needed resources to climate innovators ready to prove their technologies and deploy at scale.

Many of the most impactful programs for climate are awaiting the passage of the companion reconciliation bill still working its way through Congress. From tax credits for carbon capture to investments in clean energy deployment, the reconciliation bill will put billions of dollars more to work to fight climate change. Those billions, in addition to the billions of dollars in the private sector earmarked for ESG-positive investments, will flow toward good technologies with a demonstrated track-record. The Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations has the potential to accelerate the new energy technologies we need to ensure all those billions of dollars are put to the most effective use.

###

The Shortest Path to Circular Plastics Is Through the Chemical Companies

By Brentan Alexander, PhD, Chief Science Officer & Chief Commercial Officer and Brad Price, Principal Engineer

The last decade has seen a notable increase in public awareness of the severe impact created by the dumping of waste plastics in the environment. Images of trash covered beaches and videos of wildlife injured by plastic pollution have provided compelling visual evidence that our single-use economy is quite literally trashing our planet. Governments are starting to respond to the problem, with strategies ranging from plastic product bans to taxes, and technologies aimed at enabling circular plastics are coming to market. Enabling this transition to a circular economy requires the cooperation of the large chemical companies that make the vast majority of our plastics, and most are already on board.

It’s natural to scoff at the notion that these large multinational producers of plastic materials are a core part of a circular future. These companies, such as Chevon Phillips Chemical, Dow, and SABIC, can either directly trace their formation back to fossil-oil companies or have significant collaborations with fossil-oil interests. They’ve also used many of the same dirty tricks from the oil and gas industry: In 2020, NPR and PBS Frontline published an investigation detailing the efforts by the plastics industry in the 1980s to improve the image of plastics by adopting the now-ubiquitous three-arrow recycling triangle, despite the fact that the industry was well aware that the actual recycling of the plastic itself was either economically unviable or technically unfeasible. The parallels to the climate-denialism of the oil majors, wherein Exxon and others actively discouraged, hid, or obfuscated the evidence of human-caused climate change, are obvious.

The drive to enable circular plastics, however, is fundamentally different than the efforts to decarbonize our energy system and eliminate fossil fuels. Changing from coal, oil, and natural gas to renewable energy sources represents a fundamental attack on the future of the fossil energy majors. Circular plastics, on the other hand, are entirely compatible with the business models of the chemical giants: They take a hydrocarbon feedstock and use petrochemical processes to make plastic pellets. Switching from a fossil-derived hydrocarbon feedstock to a feedstock derived from chemically recycled plastics is no change at all. These companies have no threat of stranded assets, major business pivots, or substantial facility redesigns. To the contrary, the rapidly expanding demand for recycled plastic material represents a business opportunity for these companies on which they are eager to capitalize. The better analogy is the Montreal Protocol, in which refrigerant manufacturers that made ozone-destroying chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were central to enabling a new generation of chemicals without the same destructive impact. These companies were happy to sell a new class of refrigerants that didn’t damage the ozone layer because they were already in the business of selling refrigerants. So too are plastic manufactures fully aligned with a future built on recycled plastics.

The proof that the shift is underway can be found in the public releases of these major corporations. SABIC, Saudi Arabia’s national petrochemical company, is already selling circular plastic material at commercial scale under the TrueCircle™ brand name through its partnership with Plastic Energy. Construction is underway at Eastman Chemical’s $300+ million dollar facility to chemically recycle PET, which is expected to start up in 2022. Recent patent applications and announcements reveal that ExxonMobil is developing its own proprietary process for waste plastic pyrolysis. Chevron Phillips Chemical (CPChem), the joint venture between Chevron and Phillips 66, has entered into supply agreements with three separate startups commercializing waste plastic pyrolysis technologies. And the largest waste plastic pyrolysis plant in the world from Brightmark (an NER client) is nearing completion in Ashley, Indiana, with more larger plants on the way.

These companies aren’t spending hundreds of millions of dollars because they have suddenly become responsible environmental stewards. Rather, their investments are being driven by a changing regulatory and market environment that is providing the economic driver needed to make these investments pay off. Maine recently signed an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) bill into law that places the financial responsibility for recycling programs on the producers of plastic packaging. Other states are considering minimum recycled content mandates to require the use of recycled plastic material. Similar laws are under consideration in statehouses across the country. In the European Union, the most ambitious and impactful program came into force on January 1, 2021, when the bloc implemented an €0.80 per kilogram tax on non-recycled plastic waste.

These companies are anticipating further market growth as more regulatory programs are put in place. This doesn’t make chemical corporations full allies of the environmental movement, especially since some proposed policies will impact their bottom line. For starters, their motivations include the continued growth in plastic production globally and ever-increasing rates of plastic usage. For the developing world most impacted by plastic pollution and waste, plastics made from recycled materials pollute the beach just the same. Policies that address plastic pollution do not fully overlap with those that encourage waste plastic recycling. In many cases, plastics should be replaced by more environmentally friendly materials, an outcome that the plastics manufacturers will surely fight to avoid.

But eliminating plastic waste by eliminating plastics is not a reasonable or realizable goal. Plastics improve our quality of life, they are physically resilient, relatively low cost (even with the additional costs associated with circular material), have a wide range of uses and applications, and they perform better than competing materials. They are not going to go away. Successfully dealing with plastic’s environmental impact requires enabling circularity for the plastics that will continue to be used in our modern economy. Achieving this goal doesn’t require slaying the plastic behemoths. Instead, the fastest route to circularity lies with them—despite their checkered environmental record—and governmental policies, which need cultivation to fully enable the circular plastic revolution.

###